Elementary School Experiences

Bishop Albert Belton

Bishop Albert Belton

Bishop Belton began attended Major Bent when schools started to integrate in Steelton. There he felt the students treated him kindly for the most part, but the teachers made it difficult to enjoy school at times, “They were nice, but still, some of them were prejudice and you could tell. And you know, its hatred for no reason, so, but ah, we lived through that, it’s alright. That’s the way things were…” He explained that most children, black and white, did not grasp the concept of prejudice. Conversly, it was the teachers and parents who were prejudiced. For example, one teacher, Mrs. Ballsball, stands out in his mind: “Mrs. Ballsball had a problem with me. If I said anybody was prejudiced, I would say she would be.” Although the teachers showed the strongest amount of prejudice, the white children learned to treat Bishop Belton, and the other black children coldly after seeing through parents and teachers that iter-racial friendships violated whites’ social norms. In school, the two races got along, but after school, the two were not expected to:

I think my worst memory in school, I know that it’s the worst memory of school. The friends I had in school…alright? …would not accept our association outside school. When you are in the play, the class play and everything and you have this big production going on and everybody is getting along and we’re doing everything and then afterwards, they’re going somewhere but then, they don’t want you to go. Okay? You know you’re real tight up to that. It makes you think everything is alright and then reality hits. Its, its tough you know when you cant go to your friends’ house. Your friends love you, but they don’t want to get in trouble with your parents, you know.

Although Bishop Belton had to deal with issues of hate at a young age, he would not become embittered. He was always taught to forgive no matter what others did to him:

If there is anyone who should be angry, and prejudice, and mad, and hate, it should be me. See. Maybe that’s why God saved me. As angry as I was, I had the right kinda heart. Maybe that’s why he chose me.

Bishop Belton was raised by his grandmother, and she motivated him to excel in school. His grandmother stressed the importance of education, and prayed that he would follow through with his schoolwork, since she never had that opportunity:

She had a second grade education. She raised my mother, and then she raised me. And then we both graduated. That’s all she wanted me to do. As a matter of fact, she asked the Lord, “Lord, just let me live to see him graduate.” I graduated in June and by November she was dead. And so, He gave her, her wish.

Today, Bishop Belton greatly regrets not going to college and pursuing his intellectual hunger as his grandmother would have wanted for him to, “I should have gone to school. I was just too smart for my own self. All right? Yes! EVERYBODY GO TO SCHOOL!” Bishop Belton became very aware of the importance of education, so when his children went to school, he made sure they understood what they were there to do:

You don’t let anyone learn or listen more intently than you do. I want you to do everything. I want you to experience everything. I don’t want you to miss anything. But I want you to be the best at it. Bottom line. Apply yourself in everything you do. No short cuts, no lacking, no nothing, just do it! Pay attention, learn everything, and then achieve.

Not only does he drill the importance of education into his children, but he is also now working on building a free Christian school for those in his neighborhood who would not otherwise have the opportunity for a religious education. For him, education is a priority in life and no one, no matter what race or class he or she is, should have an opportunity to learn.

Bishop Belton summarizes his education with three words: “Love, hate, help” He experienced polar opposite feelings in school, and yet, he does not look back with any regret. Bishop Belton survived harsh prejudices throughout his lifetime in school and out, and he still feels great love for the town of Steelton and all people he has come across in his lifetime:

I am an American …and I have rights and no one is keeping them from me. Now I feel like I that I do. I’m a red, white, and blue American, believe me. I love America. Yes. I feel about America like I do about Steelton! Amen! But uh, yeah, I had some tremendous friends. As you can see though my heart, I just love. And if you do something, I’ll forgive you. I won’t let you get away with anything, but I’ll forgive you…

Joannie Poindexter

Question:

You mentioned you really enjoyed history in school…do you remember

getting much African-American history?

Answer:

Very little…uh, none, none…what was that? They didn’t even know what that

meant! (laughter) African…? (more laughter)…fifty years ago? None a that! Mm-mm, (slowly shaking head) we had none…it’s just amazing.

The thought of African American history in school back in the day when Joannie was a student makes her half laugh, half cry. As a child, she saw how she was considered a second-rate citizen by being socially rejected in school. Although Joannie smiles when looking into her old high school yearbook, she clearly still feels hurt when thinking back to how she was treated by the teachers and some of the students,”What is one thing I would have changed back then? …well I guess it would be the mentality of the teachers that showed prejudice towards the students, which I don’t see that now, really and truly.”

Joannie did not have the opportunity to go to her own prom even though she was a full-time student at Steelton-Highspire High School. African American students were not able to go to their prom as Joannie shared with me in the interview:

The schools I went to were integrated at the time, and you really didn’t get the feel of it until it came to graduation…cause we couldn’t go to the prom. It is a great, great improvement over what it used to be, because I could, we could not even go to our own prom…no…no…(shaking head) sad. So a bunch of us black kids got together …and formed a club…and by having my grandfather having a store ..the basement of the store there was a potbelly stove and a nickelodeon…and that’s where the kids used to come and dance. But we dedicated two books to Steelton schools…two black books, thats what my class did…the class of ’51, then thereafter every other class would do that, that could not go to the prom…mmhmm, we started a trend so to speak.

Although Joannie was not able to go to her school organized prom, she was allowed to go to her own graduation, unlike many other African American students at the time. Yet, this graduation was still marked by discrimination: “When I graduated, I got all kinds of accolades … uh, but they did not come directly from the school, they came from black organizations…[they] gave me my awards, not Steelton High School…”

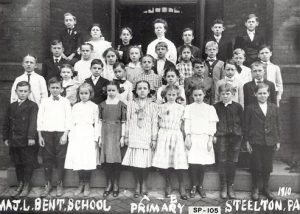

Major Bent School Children 1840

West Side School Children 1956. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania State Cultural Center.

High School Experiences

Barbara Jeane Baker

When Barbara was in high school she wanted to join the cheerleading squad, but because she was black she was not permitted to join. Today, she is very proud of her daughter who was able to be part of the team. Although she is happy to see America’s progress, she notes, “We’ve come a long way, but we have a long way to go.”

Barbara Barksdale

Barbara Barksdale

When Barbara was in ninth grade, she was fed up having to learn only about deceased white males. Aware that integration of schools was not enough, she started a “riot” in her school to increase African American awareness:

My militance came out when I was in ninth grade, when I created what they called a riot. I organized all the students and we had a little sit-in, thats what it was, a sit-in. We didn’t go to class… we sat down in the middle of the hallway, thats all we did. We said we wanted some black history… so they expelled me for a day. You know… I got hit when I got home (laughs). But I didn’t think it was right… I was fighting for my rights… and it was only fair that they taught black history and that they taught it as equal as they taught all the rest of the American history. I don’t think I did anything wrong… so you know, I’m proud to be expelled from Steelton-Highspire High School…I’ll tell the world how they treated me…see, it doesn’t make me look bad, it makes them look bad…you mean you’re gonna put the girl out because she wanted something taught?…duh!…hello! What does that say about ya?

Joyce Patterson

Joyce always enjoyed school whether she was in an integrated or segregated school, but there were many activities African Americans were kept from participating in because of their skin color in the sixties:

There were some things that, you know, there were no black Homecoming Queens or May Queens and like that back then. They would let one girl be on court or something like that, but that was it. Two years after me, when my brother was a senior, my friend in high school, her sister was her friend, ah, she was voted the Homecoming Queen…and…[the white students and administration] said, we’re gonna have a recount…and so of course, she was no longer the Queen and he got really pissed, but he was a real activist, so he declared that they would have a boycott of the cafeteria. It was a unique boycott because, you know, you figure nobody’s just gonna eat, right? Well, what they would do was like, today everybody would eat and then maybe Wednesday, nobody ate, you know, and then never knew what day they were gonna strike on…so, in the end they let her be Homecoming Queen.

Etta Payne

Etta Payne

Etta graduated from high school, but she was told as a student by the teachers and students,”Why do you want to graduate? There is nothing for you to do.” People figured that since she was black and that she would most likely end up working as a domestic, so there was no reason for her to even bother attending school. Yet, these harsh words did not cause Etta to discontinue her education, but rather, she worked hard in school and later on worked at the Harrisburg State Capitol. She was the first black woman to work with the state government in civil service job.

Steelton School Teachers. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania State Cultural Center.