Hygienic Elementary School

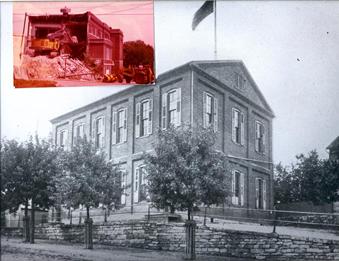

The Hygienic School was an all-black school built in Steelton, Pennsylvania in 1881 and demolished in 1974. This school was built on Hygienic Hill, and the school was named for its location. The school had only two rooms for thirty-three years, and in 1914, the building was renovated to add six new rooms. While the school was under construction, the students attended school in the basement of the A.M.E Monumental Church in Steelton. Approximately one hundred and fifty students occupied the school during a school year. Many African American children from the East and West Side came together at the Hygienic School at 175 Adams Street. Steelton was one of the last districts to follow through with integration of schools in 1958. ( From multiple sources: Stop, Look, and Listen, Football, Steelton, and the American Way)

- Hygienic School

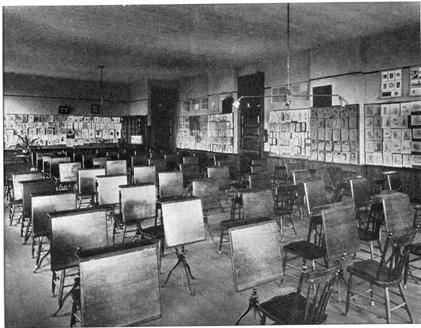

- Drawing and Art Room in 1911

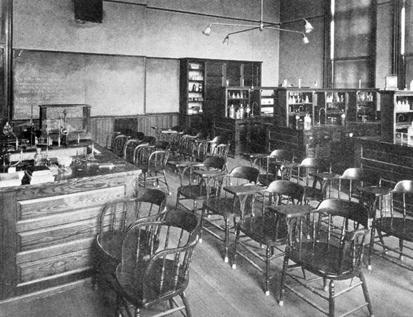

- Chemical Laboratory in 1905. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania State Cultural Center.

Experiences in a Segregated School

Deacon Ollie Allen

Deacon Ollie Allen

When in South Carolina, Deacon Allen could not go to school during the cropping months because he was expected to work, “Ahh… well, our school didn’t open up until around November or something like that and if the weather got good they would come around and shut our schools down…. But the other, I mean, white [students], they got their full nine months schoolin’.” He remembers also that he was pushed back several grades in Steelton because of his limited schooling in the South and this was determined without even an examination. When he was told he was going to be moved back, he decided to go to work instead of finishing school.

Bishop Albert Belton

Bishop Albert Belton

As a young child in the sixties, Bishop Belton attended several segregated schools, including the Hygienic school in Steelton. Belton recalls the experience with fondness: “Oh it was fun! Aww yeah! We just, aww yeah! We just had a good time! It should still be there! It shouldn’t be an empty lot! Maybe I’ll go back and build it again. Hallelujah! Yeah, that would be alright. Yeah…okay!” Belton did not regard being a student at a segregated school as problematic, because he had not yet grasped an understanding for why separate schools existed. Since everyone was black at Hygienic, children and teachers treated one another kindly, unlike in integrated schools, “I couldn’t say the level of teaching was less at Hygienic than it was [at Major Bent], you know? Cause you had the teaching with the affection. You had the teaching with the love. Someone was teaching you, not at you, you know what I mean?” Despite the fact that the facilities were not as well-funded or equipped as the white schools, Bishop Belton looks back on Hygienic fondly, because both the students and teachers treated one another with respect.

Joyce Patterson

Joyce remembers Hygienic as a place where the teachers were very strict about work and hygiene. Although the school was all-black, with fewer financial resources than all-white schools, Joyce, as well as others I interviewed, treasured their experiences at Hygienic. She describes the atmosphere as “a big family in a lot of ways. Everybody knew everybody, and you know, they knew your parents and some of them may have taught your parents.” When I asked Joyce if she was able to understand segregation as a young child, she answered:

Even when they, finally desegregated and I went to the West Side, I don’t know, it’s just some things as a child you don’t, you don’t really deal with because until somebody teaches you that there is something different about somebody else, you don’t realize it, so you play with kids and that’s just the way it is.

Although Joyce was not aware of the separation as a child, as an adult she comments: “I just think [segregation] was sad. You know, there’s nothing you can do about it, you know. It’s sad that people think that way or feel that way, especially when they create problems for kids that they…could affect their whole lives”