Contemporary view of African American Hairstyles.

Photos courtesy of Hair Stylist Online.

“The way we talk, the way we walk, sing, dance, pray, laugh, eat, make love, and finally and most important, the way we look, make up our cultural heritage. There is nothing like it or equal to it, it stands alone in comparison to other cultures. It is uniquely, beautifully and personally ours and no one can emulate it.”

-Barbara Ann Teer, 1968

African American women’s search for societal acceptance often encompasses struggle between natural and socially constructed ideas of beauty. As an essential component in traditional African societies, cosmetic modification is ritualized to emphasize natural features of blackness. Defined by social occasion such as childhood development to maturity, indicators of marital status or the group to which you belong, beautification of the hair and body play an essential role. In our racially conscious society, presenting a physical image and being accepted is a complex negotiation between two different worlds.

Mrs. Corbin

Lois Corbin, an experienced hairdresser in the Harrisburg area, has seen styles come and go. She owns and operates her own salon and caters to the many different needs of her life long customers. Not only is her salon a place where hair styles are created, but it is also where confidence and relationships are built. Here Mrs. Corbin talks about how hair is both a physical and emotional statement.

Hair is an outward expression of culture and heritage. It also represents a sense of personal style. In the search for the African American identity, blacks have undergone many different changes in hairstyle. Hairstyles are cultural classifiers of what African Americans consider beautiful. Hairstyles are a representation of the African American soul, all of their confidence and dignity show in how they present themselves on Sundays and on a daily basis. Van Deburg text states, “Soul was the folk equivalent of the black aesthetic. It was perceived as being the essence of the separate black culture. If there was beauty and emotion in blackness, soul made it so. If there was a black American mystique, soul provided much of its aura of sly confidence and assumed superiority. Soul was sass- a type of primal spiritual energy and passionate joy available only to members of the exclusive racial confraternity” (195). Therefore, the concept of soul style aided Black America’s individual and group self-definition. Complimenting the soulful styles of women is the “natural” hairstyle. “During the sixties, white American youth used their hair to make a variety of political and philosophical statements” , young blacks joined thereafter (Van Deburg 201). The natural hairstyle not only was easier to care for, but also gave African Americans a closer tie to their heritage. The natural hairstyle became a trend who’s history ran deeper than merely fashion. Natural style serves as ãa visible imprimatur of blackness; a tribute to group unity; a statement of self-love and personal significance” (Van Deburg, 201). By rejecting the white standards of beauty, black Americans halted the processes of using chemical straighteners or hot irons.

Black natural is beautiful. Photo courtesy of Cooper, Hair.

Often women’s hair is teased, sparkled, sprayed and intricately decorated with beads and shells; styles which demonstrate the influences of traditional African techniques such hairstyles

represent a tribute to their ancestors and ultimately signify an expression of Arfrocentricity. Proud of their roots as African’s, blacks celebrate their heritage through natural hairstyles.

African American Genie McMurrick talks about her struggle. “I remember battling with the idea of going natural for several years. I never had the courage because every time I pictured myself with my natural hair, I never saw beauty. Now my hair is natural, thick and healthy. Yet, it saddens me to know that at one point in my life I felt being natural wasn’t beautiful.” (“Natural…”1). African American women are finding confidence within themselves to wear their hair naturally and feel beautiful about it.

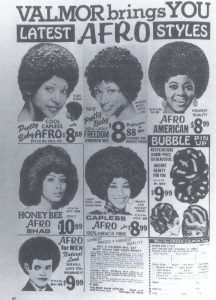

African American wig advertisement. Photo courtesy of Van Deburg, Babylon

“Afrylic” and “Afrilon” natural wigs were also popular alternatives to the rigors of everyday styling of real hair. Wigs are a pre-set style, easy to maintain and less time consuming. These wigs are often marketed under names such as “Super Afrique,” “Afro Bunny” and “Nubian Queen” (Van Deburg, 201). The natural hairstyle is a symbol of black cultural autonomy, and psychological “debrainwashing.”

“Hair is a nonverbal part of communication passed on from generation to generation” -Cathy Gant-Hill.

Francis Ward experienced the legacy of being torn between African and Anglo cultures during her Sunday hair straightening sessions with her grandmother, her hot comb and stove burner. As she grew older, Ward realized she and many other women were assimilating to try to get what was closest to “good hair.” “Her mother or her grandmother never told her her natural hair was not suitable. But their actions spoke an eye-opening truth to Ward” (Cathy Gant-Hill).

“Good hair” has been defined as long, straight and therefore beautiful” (African Amer. Org.). “Good hair was the hair that bounced and shook. You saw it in all

Straight isn’t necessarily beautiful. A representation of straight hair being “good hair.”

Photo courtesy of African American Organization.

the shampoo commercials, the white lady with the hair bouncing around, and you were told that was good hair. No one ever defined what bad hair was” (Cathy Grant-Hill). Women seeking solutions come to focus on artificially changing their natural hair structure. African American women have been trying to manipulate, control or find solutions to their “hair problem” for years. Through “the process of lye, making one’s hair straight is a practice that has made textured hair and people of color somewhat acceptable in the white world” (“Rooting…2).

However, many contemporary African Americans are avoiding high maintenance and feeling confident in their natural beauty. As African Americans began to realize that they were being oppressed and their natural looks were beautiful, “Malcolm X expresses that shame was the motivation behind blacks losing their roots and ethnic identity” (McMurrick 2). By being brainwashed into believing black people are “inferior” and white people are “superior” African American’s mutilated and adjusted their bodies to try to look “pretty” by white standards.

Braids are a popular hairstyle for African American women.

Photo courtesy of Hairstyles Online.

“Now we don’t have Afro’s, but we have sisters who are bald- headed, people wearing curls and weaves. I can’t even keep up with all of the hairstyles. It’s anything now, and that’s good. There should be a proliferation of style” -Francis Ward.

Americans spend billions of dollars in the quest for beautiful hair. African Americans share the experience of finding their hair identity. Ethnic hair care products are a lucrative market in the beauty industry as companies are finally adding more products targeting black and non white women.

Hair is as different as the people it belongs to. People are finally recognizing that beauty is what helps to create our individual identities. Ultimately, individual confidence shapes and strengthens the culture of the African American community.