Over the past 20 years of climate negotiations, nothing substantial has been accomplished in terms of mitigating global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Only those countries that have the most to lose from climate change, i.e. sovereignty, have pushed for meaningful action. This has led to a lack of significant commitments by major polluters, and international organizations such as the United Nations (UN) have failed to enforce mitigation strategies. Realism provides the strongest lens through which to see and understand the path of the global climate change negotiations and provides the best predictor for how states will act in this arena moving forward.

States function in an anarchic system, and thus climate negotiation between all countries also face the challenges of anarchy. There is no one group that can control the states and force everyone to agree on any one path to action. It can be argued that the UN brings all of the states together for the discussions and that they dictate the schedule, but the UN has not exemplified the ability to inspire or force any decisions to be made. The United States, the world’s second largest emitter of GHGs, acts as hegemon in the climate negotiations (Bulkley and Newll, 2010) and is able to maintain no binding international regulatory measures on GHGs. When the US senate passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution the Kyoto Protocol lost global emissions reductions significance. When the hegemon backed out, it unraveled the Protocol, proving that the most powerful must be integrally involved in order to have effective results. According to a realist point of view, if the US, instead of backing out, had used its political and military power to enforce a strong agreement, the Kyoto Protocol could have come into force for all states; however, that would not have been in the best economic interest of the country, which means that they would not enforce the Protocol.

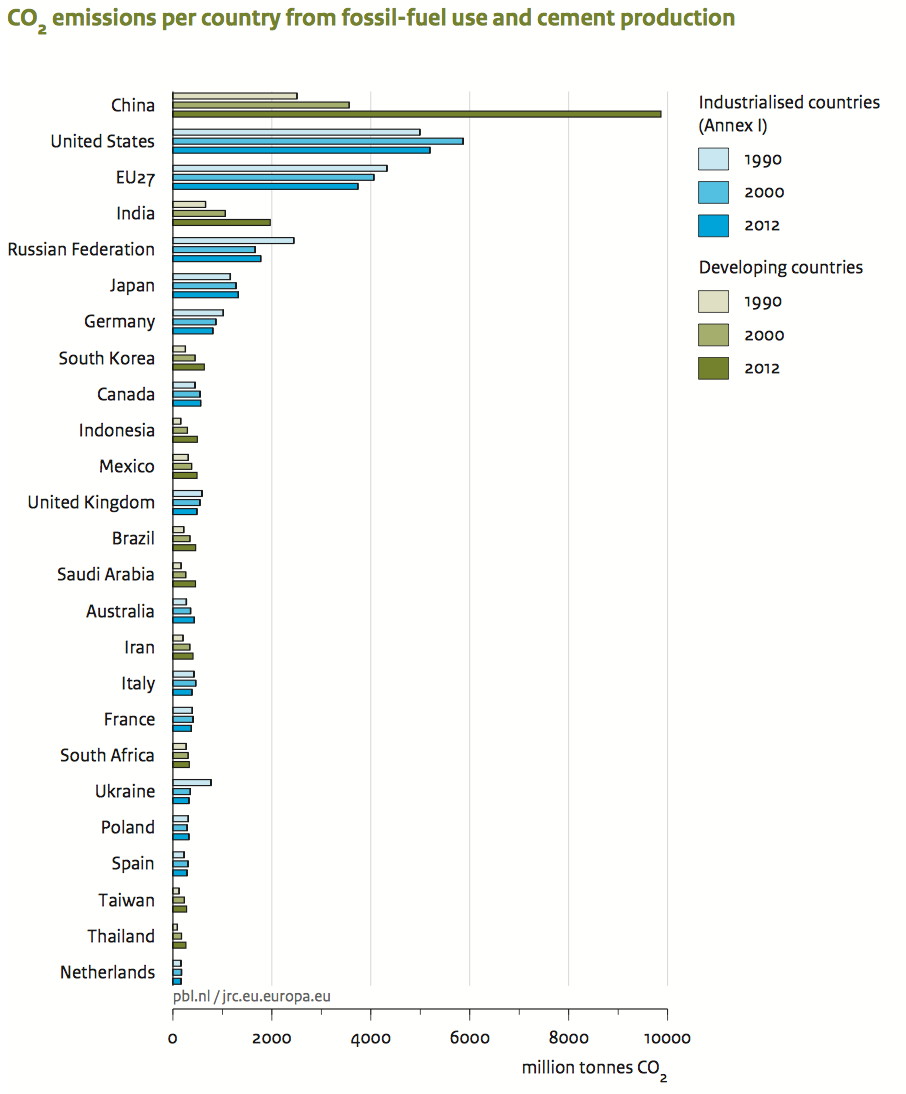

Constructivism does not work as a model to fully explain global climate negotiations because communication and involvement from non-state bodies is not leading to cooperation by the involved parties. The negotiating parties are not accepting norms and ideas, thus there is no currently plausible mechanism for mitigating global GHG emissions. It is simply not in the economic self-interest of powerful states to slow growth and prevent the use of fossil fuels. In this light, the realist point of view describes inaction from the most carbon intensive states because they have an intrinsic self-interest in continuing to burn fossil fuels. This is not to say that these nations would not receive some benefit from pollution reductions such as cleaner air, but currently their personal cost is much greater than any benefit they may receive.

Using the realist theory we can explain why some parties, such as the Alliance of Small Island States, who are most vulnerable to climate change (Bulkeley and Newell, 2010) are already taking action. From a realist point of view, small island states would only voluntarily cut back on emissions if they would directly benefit from those actions. These nations risk loosing their sovereignty due to sea level rise, so it is consistent with a realists understanding for these most vulnerable countries to cut their emissions to attempt to spark international change. When faced with losing an entire nation, it is expected that the population would be as vocal as possible to attempt to save their sovereignty. As Fletcher (2013) describes, Costa Rica is taking action after increasing political pressure in the 1980s to stop deforestation. After accepting funding to help these efforts, Costa Rica has become a global model for carbon emissions reductions and forest preservation. The European Union has taken more significant action than any other powerful and significant state in terms of GHG emissions. The EU and states that have taken action on climate change have not done so because they are good global citizens. They have done so because they are vulnerable to the effects of climate change and will be better off as a state (or grouping of states) if they take actions to preserve environmental services and reduce GHG emissions. Even though these actors and other states have been cooperating on small actions, a realist view still most accurately describes the climate negotiations because there has not yet been collective action by all global parties.

The only way states will be able to agree to a binding agreement on GHG emissions, under this realist theory for international relations, would be for a hegemon to take charge of the negotiations. The hegemon or another powerful state that could compete with the hegemon for that position would have to successfully threaten the use of force to make other states comply with mandatory GHG reductions. With a lack of such a leader and a global government, it is highly unlikely that this outcome will occur. Countries will continue to negotiate around climate change until the cost of inaction becomes too great and it is no longer in a hegemon’s best interest to continue to allow excessive GHG pollution.

Work Cited

Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell. Governing climate change. Routledge, 2010.

Fletcher, Robert in “Climate governance in the developing world.” Reference & Research Book News 2013: Academic OneFile.

Trends in global CO2 emissions: 2013 Report. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. European Commission Joint Research Center. 2013.

This is a very interesting post, Will, and was very thought-provoking for me because I approached this in a completely different way. I disagreed with your assessment of the United States hegemonic power; following the realist train of logic, if a hegemon abandons an agreement in the way the US did with the Kyoto Protocol, it should be expected that the agreement would falter and fail. This is what you purported above, but, from the evidence I’ve seen, this is not the case; after the Byrd-Hagel Resolution in 1997, the rest of the world didn’t fold and give up on the agreement, but were energized into filling the void that was left and putting Kyoto into practice. The Russian Federation, Japan, the European Union as a whole and most of its member countries individually all ratified the treaty after the US pulled out, which was enough to not only put it into force, but also to meet and exceed its first round emissions reductions benchmarks (12.1% reduction from Parties with targets, 4.7% Kyoto target reduction; IEA, 2013, p. 16). So, I think to call Kyoto a failure, especially after the US reneged, is a misinterpretation of what actually happened and to have a perspective on international relations that may make sense on paper, but doesn’t make sense when applied against real-world events.

Hi Brady, thanks for responding to this. I agree with you, I think that the US is not a true hegemon and that we are kidding ourselves to think that we can control global negotiations. I do think however, that the US plays a key role in these negotiations and that unless the US is part of a binding agreement, it won’t be effective. We are too polarizing, big, and historically powerful too not be part of a meaningful climate deal. What I said in this essay does not necessarily reflect what I personally believe, I believe some of it, but I think that the part that you are highlights is not my opinion. I was attempting to write the paper from a pure realism perspective, and while it might not be a perfect match, it was what I saw as the realist point of view and it fit nicely. Does that make sense? We should talk about his more in person if you are interested.