The looming uncertainties of climate change are an imperative call-for-action for swift international cooperation between nations in order to reduce emissions and “to achieve…stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.”[1] But is it really practical to expect such universal and broad-based partnership among nations with such drastically polar interests, perspectives, and opinions? An analysis of the historical evidence shown from previous climate governance negotiations, commitments, and actions validates the liberal school’s expectation of international cooperation over a realist’s skepticism moving forward in efforts to mitigate climate change.

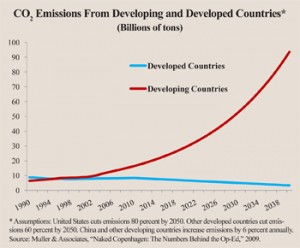

The realist school of international relations theory argues that nations act out of their own self-interest and from a fundamental struggle for power over other nations, and thus hardly ever cooperate on an international level.[2] However, such cooperation is the main force for action in the climate governance arena; the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has produced significant agreements[3] by major international actors aimed at greenhouse gas emissions reductions, which endorses the liberal institutionalist school’s assertion that international institutions “mitigate anarchy and facilitate international cooperation.”[4] Large numbers of nations from all different backgrounds have taken action through the UNFCCC structure to reduce emissions, whether through legally-binding commitments (Annex I nations) or on their own accord (non-Annex I nations). Forty-four developing countries have submitted Nationally Accepted Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) from 2009 to 2012[5] outlining their plans to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions while under no legal obligation to do so, which contradicts the realist assertion that, when given the opportunity to, a nation will free-ride off the efforts of another.[6] This elevation of the common good over national self-interest undercuts realism’s core tenet that all international relations are inherently power struggles; nations of sometimes opposing stances (e.g. the current tension between the Russian Federation and the European Union over Ukraine) have put aside their differences and taken meaningful international action to address the growing specter of climate change.

A strong example supporting liberalism is the Kyoto Protocol. If realism were true in climate governance, it would have been expected for the agreement to have floundered and failed after US pulled out of the negotiations in 2001; however, “…the absence of the United States served to galvanize the European Union and G77 + China into further action, and with the Russian ratification of the Kyoto Protocol in 2005 it entered into force.”[7] This signals that the international institution of the UNFCCC and the cooperative attitudes of many nations in the negotiations prevail over actions of single nations, and verifies the general alignment between climate governance and the liberal school of thought.

A major factor in the liberal framing of cooperation is the concept of confidence-building measures, which “develop the trust and confidence necessary for resolution of larger conflicts.”[8] Previous agreements made during the UNFCCC function in this capacity, as progress has already been made, but there is still more work to be done. Emissions for all Annex I parties (most of the major emitters of the world) including the US have decreased by 6% from 1990-2008[9] and “together, the commitments made by developed and developing countries cover more than 80 per cent of global emissions, and, if delivered, could reduce emissions from BAU by 6.7-7.7 billon tonnes.”[10]

One of the criticisms realists argue against international institutions like the UNFCCC is that there is a lack of enforcement of a nation’s actions as they align against their previous commitments, and, thus, anarchy reigns in the world politics. However, the enforcement arm of the UNFCCC ensures that nations not just give “lip-service” to emissions reduction but actually follow through on their commitments, with the threat of strict penalties and increased emissions reductions targets.[11] This added accountability lends strength to the negotiation process and final commitments agreed upon by the Parties, and mitigates anarchy by restricting nations’ behaviors.

Given the evidence presented by previous agreements and negotiations, climate governance can best be described through the liberal school’s lens rather than realism’s because of the scope and durability of international cooperation that has been previously observed. It can be expected that, moving forward in the coming years and at COP20 in Lima in December, this broad-based partnership and interaction between nations can be the rule, and not the exception.

[1] “Article 2: Objective”, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, accessed September 11th, 2014. http://unfccc.int/essential_background/convention/background/items/1353.php [2] Russell Bova, How the World Works: A Brief Survey of International Relations (New York, NY: Longman Publishing, 2011), 8-19. [3] Namely the Kyoto Protocol (2005), the Bali Action Plan (2007), the Copenhagen Accord (2009), the Cancun Agreements (2010), and the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (2012). [4] Bova, 21. [5] David Held, Charles Roger, and Eva-Maria Nag, Climate Governance in the Developing World (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2013), 3. [6] Bova, 241. [7] Harriet Bulkeley and Peter Newell, Governing Climate Change (New York, NY: Routledge, 2010), 23. [8] Bova, 20. [9] “Compilation and synthesis of fifth national communications: Executive Summary”, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, accessed September 11th, 2014. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2011/sbi/eng/inf01.pdf [10] Held, Roger, and Nag, 3. [11] “An Introduction to the Kyoto Protocol Compliance Mechanism”, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, accessed September 11th, 2014. http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/compliance/items/3024.php