By Maeve Hogel

When examining different situations, people are often described to have a glass half full or half empty point of view. The glass half full people are the optimists, who always see a positive in any situation, whereas the glass half empty people tend to dwell on the negatives. In international relations, there are contrasting theories that in many ways reflect the glass scenario. Looking at the situation of climate change, realists believe that nations states’ personal interest for power will always come first, while liberalist think the self-interest can be overcome to obtain cooperation (Bova, 9-21). The voluntary efforts of many developing countries such as Costa Rica and Brazil demonstrates that liberalist theorists might just be correct that countries can reach cooperation when there is a mutual gain for everyone, not just for themselves.

It is important first to understand liberalist theory better to see how climate change fits well under its beliefs. Liberalists are not naïve to human nature’s draw to make decisions based on self-interest. However, “liberal internationalists see many issue areas in which states have a strong mutual self-interest in working together to achieve absolute gains for the common good” (Habib, 14. Found Here). Although places may be affected to different extents, no country is safe from climate change. All peoples and countries share the environment therefore cooperation is completely necessary to combat the issue. However, being such a global issue gives countries an even stronger “mutual self-interest” in the matter. Liberalists believe, not that countries would act without receiving any personal gains, but rather that every country will receive a mutual gain which is what will lead to cooperation among all.

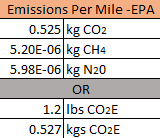

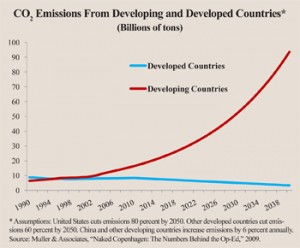

David Held, Charles Roger and Eva-Maria Nag in their book, Climate Governance in the Developing World, provide several examples of countries whose individual efforts support the liberalist view that cooperation is possible. Developing countries, referred to as non-Annex 1 countries in climate policy speak, are responsible for about half of GHG emissions (Held, 7). Although historically now developed countries, such as the United States and Europe, caused the rise in temperature, developing countries will be continuing to grow in the future and therefore are crucial to climate change negotiations. If realists were correct, the self-interested, power seeking countries would gain most from continuing to grow and industrialize, telling the developed countries to essentially clean up the messed they caused. However, after the Copenhagen Accord in 2009, developing countries were able to make commitments called Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs). These were not required but 44 developing countries decided to make a commitment to reductions of emissions by their own choice (Held, 3).

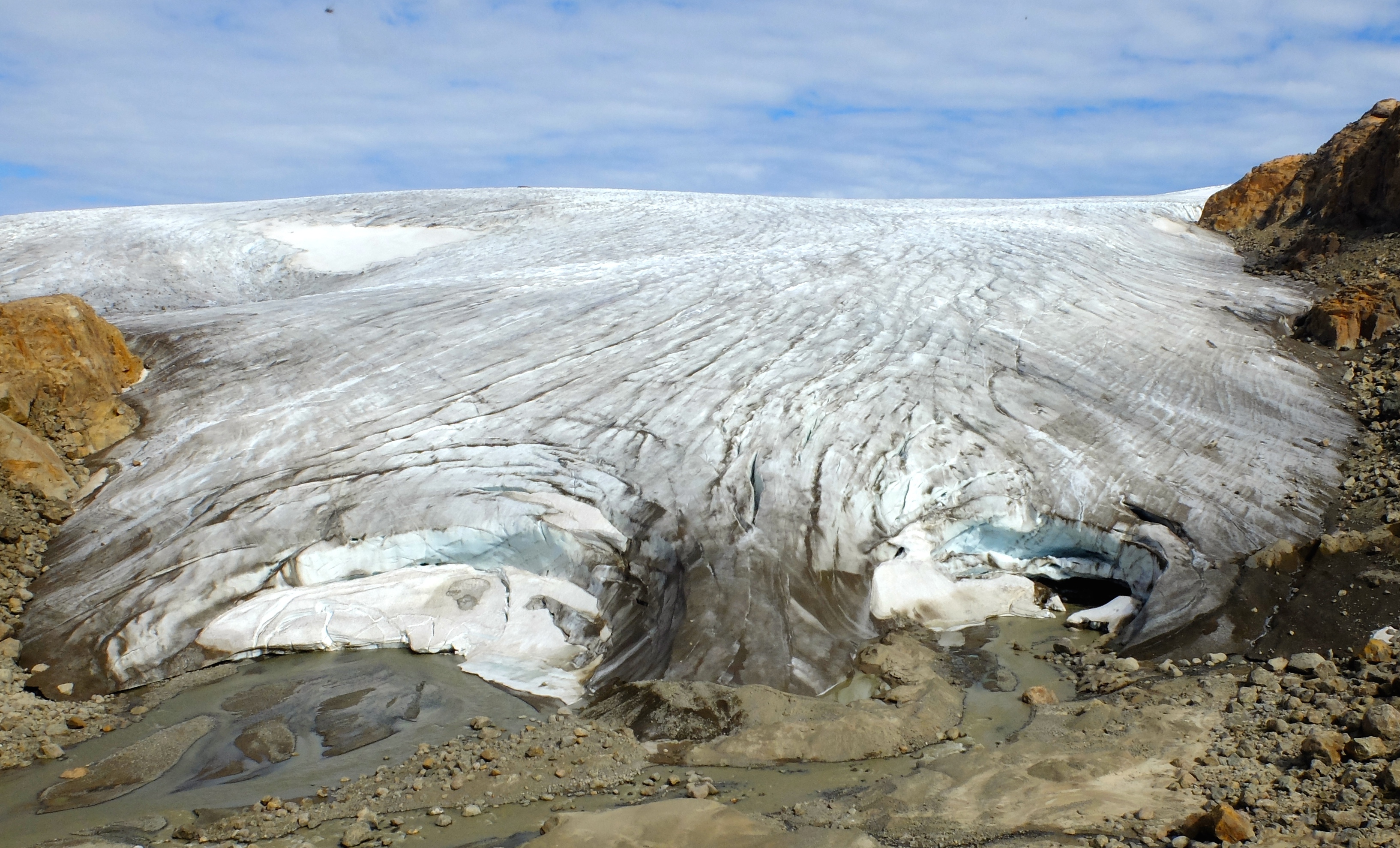

Brazil and Costa Rica are among several developing countries that have gone above just a NAMA commitment and have really been leaders in climate change initiatives. Brazil, a country that has seen rapid economic growth and is a larger emitter due to deforestation, has made large efforts to cut back on deforestation and to decrease their emissions in that past several years (Held, 13). Costa Rica is a tiny country in comparison to Brazil and has not seen anywhere near the same rapid expansion and growth . Costa Rica though, like Brazil, has made big voluntary efforts to reduce their emissions. With a history rich in deforestation as well, Costa Rica has vowed to go many steps farther then Brazil in hoping to be the first carbon neutral country (Held, 14).

Brazil and Costa Rica are not by any means the only countries to be voluntarily attempting to reduce their emissions. However, these two countries exemplify the liberalist’s belief that cooperation will be possible since all countries will gain, in the long run, from stopping the planet from continuing to warm. Of course there is still a long way to go when it comes to cooperation on climate change policies and initiatives and there are still plenty of countries that are not making large voluntary efforts. However, no one is saying the glass is completely full just yet, but it’s certainly not half empty.

Held, David, Charles Roger, and Eva-Maria Nag. Climate Governance in the Developing World. Cambridge, 2013. Print

Bova, R. How to think about world politics, realism and its critics. 2011.

Habib, Benjamin. Climate Change and International Relations Theory. 2011.