The Kyoto Protocol, the first legally binding international agreement on climate change that pledged parties to emission reduction targets, had a commitment period lasting from 2008 until 2012 (UNFCCC Kyoto). Now that this period has ended, climate negotiators are concerned with trying to create a second commitment period to reduce GHG emissions. Scheduled to end its work in 2015, the date by which a protocol or international agreement should be completed, the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) is tasked with developing a protocol or other agreement with legal force (UNFCCC Ad Hoc). There are a multitude of ways to go about this–most broadly, the three options are a top-down, a bottom-up or a mixed-track approach.

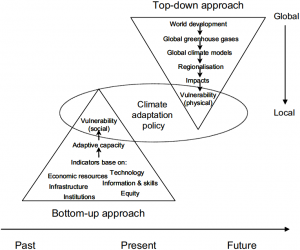

A top-down approach to climate change would mean that after an international greenhouse gas concentration target is agreed upon, both the manner in which a country will achieve this goal, and individual country targets, will also be decided upon internationally through a general allocation formula. The opposite of this, a bottom-up approach, would consist of an agreement to allow states to define their commitments individually. The Kyoto Protocol was somewhere in between these two approaches, and was considered a mixed-track approach. Emissions targets were decided upon internationally, but this number was merely a sum of individual national commitments, and countries had very different emission reduction targets that they were able to decide partly on their own (Bodansky 4).

Moving forward, the next step should be one that lies somewhere in between a mixed-track and a bottom-up approach. It should take into account the agreed upon limit for rising global average temperature–2 degrees Celsius–and also allow countries to decide in what manner they want to go about reducing emissions.

An international agreement, as Daniel Bodansky explains, is “not only…the stringency of its commitments, but also the level of participation and compliance…” (Bodansky 2). The problem with a top-down approach is that it is tough to get the participation of a wide range of countries because each country has different economic capacity, poverty levels, and economic diversity. Make it too stringent, and more countries will reject it. The only way to get a substantial number of countries to accept an international agreement is to make it less stringent, which won’t have enough of an impact on global emissions to substantially mitigate global warming (Bodansky 2). A bottom-up approach is much better for reducing global emissions, as more participation from countries is inevitable because they will have the freedom to implement actions based on their economic capacity, growth rates and their amount of survival emissions. But there is one glaring concern with this bottom-up approach, which is that letting individual Parties decide for themselves what measures to take might result in a lack of ambition. Countries might be more concerned with their economies in the short run, rather than with mitigating climate change, and will enact less stringent measures than they would in a top-down approach.

At COP16 in Cancun, the Parties agreed to a maximum temperature rise of 2 degrees Celsius (UNFCCC Cancun). Actions implemented by countries should be dedicated to controlling emissions to a point that would prevent temperatures from increasing more than that. To counteract subpar ambition in mitigation actions, Bodansky says, a legal agreement could be created stating that national targets and actions need to be judged by a panel of international experts both ex ante and ex post to make sure actions that are taken will be able to keep warming at or below the agreed upon 2 degrees Celsius limit (Bodansky 9). This might be a little harder to implement in an agreement than in a pure bottom-up approach, but because the Parties have already agreed to keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius, it is much more likely for them to agree to this than, say, expanding agreements under the Kyoto Protocol, in which countries have already expressed disinterest in (Ministry).

On October 1, 2014, David Victor and Charles Kennel, in the journal Nature, argued that the 2 degrees Celsius limit should be ditched in favor of testing conditions such as CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, ocean heat content and temperature in the Polar Regions to track the stress humans are putting on the environment (Victor). They argue that these measurements are better indicators of human stresses on the environment than the global average temperature. While this may be true, the fact that world leaders have accepted 2 degrees Celsius as the highest acceptable amount of warming is a huge step, and must be taken into account in the ADP’s proposed second commitment agreement. To try and change this will slow international climate negotiations down significantly. But, moving forward from this 2nd commitment period, it might be possible to have Parties accept different indicators of global warming in the future. As Bodansky states, strong participation with less effectiveness can lead to strong participation and more effectiveness in the future, while less participation and more effectiveness might be held back by the fact that narrow participation can lead to carbon leakage and competitiveness concerns. (Bodansky 2). If a legal agreement can be forged that allows states to choose individual emission-reduction techniques and targets, but is able to make sure they are strong enough to meet the 2 degrees Celsius limit that has already been agreed upon, it might be possible to have strong participation with moderately strong effectiveness, and such effectiveness may only get stronger in the future.

Works Cited

Bodansky, Daniel. The Durban Platform: Issues and Options for a 2015 Agreement. Publication. Arlington, Va: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, 2012. Print.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Foreign Policy. Japan’s Position Regarding the Kyoto Protocol. MOFA. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Dec. 2010. Web. 8 Oct. 2014.

UNFCCC. “Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action.” Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. UNFCCC, 2014. Web. 08 Oct. 2014.

UNFCCC. “Cancun Climate Change Conference – November 2010.” Cancun Climate Change Conference – November 2010. UNFCCC, 2014. Web. 08 Oct. 2014.

UNFCCC. “Kyoto Protocol.” Kyoto Protocol. UNFCCC, 2014. Web. 05 Oct. 2014.

Victor, David G., and Charles F. Kennel. “Climate Policy: Ditch the 2 °C Warming Goal.” Nature.com. Nature Publishing Group, 1 Oct. 2014. Web. 08 Oct. 2014.