A comprehensive international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is derived from the need to halt human-induced shifts in the climate system as soon as possible. These shifts are dependent “on cumulative emissions rather than on emissions at any particular point in time” or place for that matter.[1] There may be some nations, such as China or the United States, that need to reduce their emissions significantly more than others, but they cannot be the only reductions. Every other nation that is party to the UNFCCC must make reduction efforts if there is to be a holistic commitment by the entire international community. This means that nothing can fall through the cracks, which has been seen in past “top down” and “bottom up” approaches. A less rigid and more all-inclusive agreement needs to be reached. This agreement will have to come in the form of a “mixed track” initiative in order to allow for the flexibility needed by the broad range of interests displayed in the Parties.

This new agreement will come out of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP), whose directive is to “develop a protocol, another legal instrument, or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties.”[2] The ADP is also charged with having this agreement ready for the 2015 negotiations. This would allow for it to be adopted and for implementation to begin in 2020, at the end of the extended Kyoto Protocol.

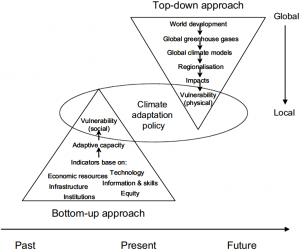

This new instrument will need to address the issue from a new perspective, as old agreements have not been comprehensive enough. A “mixed track” initiative would allow for flexibility and what is termed as “variable geometry” within the negotiations.[3] What this means is that certain parties would be able to take up different pledges in order to meet requirements set out for their particular region. This approach is not the one-size fit all that has been seen in the past. It avoids some of the pitfalls experienced by the stricter “bottom up” and “top down” approaches. An example of improvements to be made on the “top down” approach can be seen in the Kyoto Protocol’s lack of flexibility in developing emissions reductions targets. A more flexible approach would allow for non-absolute targets and allow for more participants, while promoting equity through nationally appropriate targets. This level of flexibility can be seen in the “bottom up” approach style, however the dependence on domestic governments in the development of national protocols has held some nations back from developing plans.

The “mixed track” approach would offer the “variable geometry” that Bodansky mentioned. Nations would be able to develop a plan for emissions reductions, while still acting under the international regime target of emissions reductions, and have a higher likelihood of meeting that plan- seeing it was developed with domestic interests in mind. An issue of complexity does come to my mind when I think about this approach. Developing a system that could capture the many interests and needs of the international community without duplicating processes could prove to be difficult. But, no system is going to be a simple design. If this “mixed approach” could be agreed upon and developed it could get the job done.

Works Cited

Bodansky, Daniel & Elliot Diringer. 2010. The Evolution of Multilateral Regimes: Implications for

Climate Change.

Pew Center on Global Climate Change, Arlington, VA. Bodansky, Daniel. 2012. THE DURBAN

PLATFORM: ISSUES AND OPTIONS FOR A 2015 AGREEMENT. Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, Arizona State University.

UNFCCC/CP/2011/9/Add.1

[1] Bodansky and Diringer, 2010 [2] UNFCCC/CP/2011/9/Add.1 [3] Bodansky, 2012