By Elizabeth Plascencia

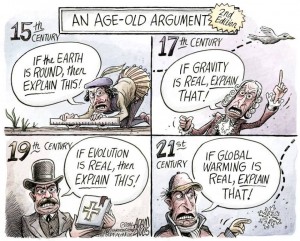

Evidently realists will be realists, I will be me, and you shall be you. Set on a trajectory of thought spanning from the latter end of World War II, realism, as a paradigm, populated the gamut of international relations, which felt seemingly appropriate for its time. Strikingly similar to that of the second law of thermodynamics, entropy or chaos, was at an all time high post-World War II, in which case a realists’ pessimistic stance deemed valid. Within R. Bova’s text, How the World Works: A Brief Survey of International Relations, he boldly states, “At this point, however, no single paradigmatic challenger to realism has emerged”, where I contentiously yet mindfully respond. Today, September 12, 2014, I challenge the realist paradigm on the sanction of qualitatively and quantitatively significant evidence extrapolated from the liberalism paradigm of international relations theory.

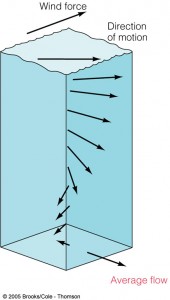

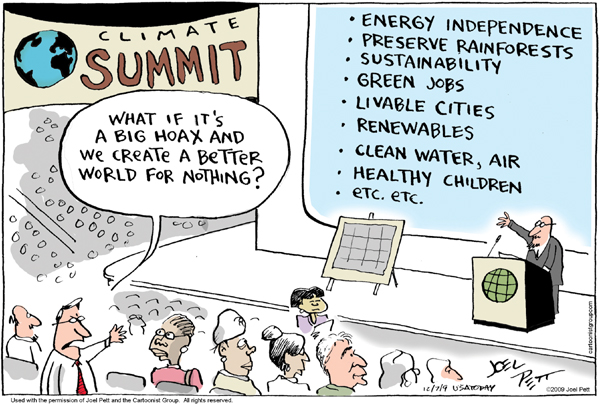

In essence, liberalism speaks to the ever-changing nature of world politics and opens the window to optimism that realists’ blocked with stagnant anarchic assumptions for the rest of the world. In lieu of qualitative evidence negating Bova’s statement, “In short, for realists, the expectation that global environmental crisis will lead to cooperative responses is both naïve and contrary to the record of human history”, the unity of liberal internationalism, liberal commercialism, and liberal institutionalism creating the Kantian Triangle[1] are highly regarded (pg 249-50). The UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) is an outstanding example for a liberal institution that promotes peaceful cooperation on an issue as pressing as global climate change. Moreover as presented by the National Research Council within “The Context for America’s Climate Choices” the United States “…endorsed an effort to work with the international community to prevent a 2 (3.6 ) increase in global temperatures relative to pre-industrial levels” (pg. 11). Furthermore providing evidence framing single nation and multi-nation cooperative initiations that are making active efforts to mitigate climate change.

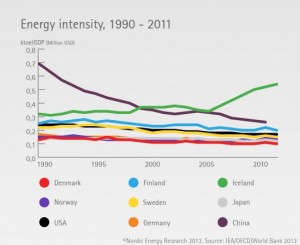

Within a working liberalism paradigm there exists this notion of “absolute gains” [2] which is derived from cooperative and peaceful state interactions. Whilst keeping a focus on absolute gains, a liberalist sees no reason to compare their gains to that of another nation. In fact, quantitative statistical analyses as presented by the International Energy Agency reveal that “The Australian government and European Union had announced intentions to link their systems, starting with one-way trading of European allowances into the Australian market from 2015, followed by two-way linking from 2008” and “In December 2008, the European Council and the European Parliament endorsed an agreement on climate change and energy package which implements a political commitment by the European Union to reduce its GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions by 20% by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. The package also includes a target for renewables in the European Union, set at 20% of final energy demand by 2020” (pg. 17).

As previously stated – realists will be realists, I will be me, and you shall be you. Derive what you will from the empirical trends, but know this – if anarchy is what they think, anarchy is what they will get.

Footnotes:

[1] Kantian Triangle – Idea that international institutions, economic interdependence, and the diffusion of democratic government are mutually reinforcing and together support liberal notions of a trend towards peace and cooperation among states (Bova, 22). [2] Absolute gain – the total benefits that accrue to a state as a consequence of its interactions with other states without regard to the benefits that accrue to others (Bova, 19).

Works Cited:

Bova, R., 2011, “How to think about world politics, realism, and its critics” How the World Works: A Brief Survey of International Relations, Longman Publishing, pp 3-37.

Bova, R., 2011, “Transnational challenges, the state system under stress” How the World Works: A Brief Survey of International Relations, Longman Publishing, pp 237-250.

International Energy Agency, 2013, CO2 emissions from Fuel Combustion, Highlights, pp 7 – 19.

National Research Council, 2011, “The Context for America’s Climate Choices,” in America’s Climate Choices, pp 7 -14.