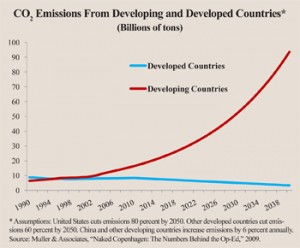

It is undeniable that the current global climate crisis is unprecedented in international relations. It is an issue of critical importance as it affects each nation at varying degrees and each nation contributes to the problem, in extremely varying degrees. Global climate change, by its nature, necessitates strong, unified global action. However, there is a difference in international relations theory that attempts to understand how and if this transnational cooperation will happen. Realism is a paradigm that asserts that all international relations are based on a struggle for power between sovereign states in an anarchical world. This approach believes that nation states are only interested in their own security and so all actions are defined by the notions of “self- help” and the “security dilemma;” thus cooperation between states to create a system of global governance is impossible. However, liberalism is a paradigm that suggests that perhaps the opposite is true with a different set of international norms and institutions that would facilitate international relations based on cooperation not military might and power insecurities. According to Russell Bova, liberalism holds that, “as long as your state is better off as a result of cooperating with others, the gains of others should not matter” (Bova 19). Certainly, in the issue of climate change each nation would be better off by addressing the tragedy of the commons and cooperating to mitigate the problem. Actions and cooperation already in affect by the international community intend to deal with how to mitigate and govern global climate change, follow the paradigm of liberalism.

Global climate change has forced international cooperation on a smaller but quickly growing scale. There is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), an international scientific community to inform the policy makers on the science behind the problem. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is a treaty created and being implemented by many sovereign nations attempting to cooperate to confront climate change. They also continuously further their cooperation to create better governance through the Conference of the Parties (COP). Out of this international process, the Kyoto Protocol was created in attempt to legally require international participation and cooperation to limit greenhouse gas emissions. There is much speculation on whether or not the Kyoto Protocol was “successful”, however, it is an example of a potential base line for future legally mandated international cooperation. There has also been further and more voluntary cooperation on global climate change, specifically by developing counties, attempting reduce greenhouse gas emission, through the Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMA). The fact that these actions were all voluntary and were not based on power play between nations implies that there is reasonable evidence that climate change can be regulated globally through continued mutual support and cooperation.

The efforts to govern climate change mitigation through a liberalist mentality have certainly been present in the last couple of decades. While the results have largely been nominal in actually preventing or lessening climate change, the fact that it is happening at all, and is building off of itself to continuously create better cooperation is promising. The prisoner’s dilemma for realists is a way of explaining how parties will inevitably act in their own self-interest, to assume the least consequences. However, the liberal interpretation ends in a scenario that is already playing out in the global action and negotiation of climate change. In this prisoners dilemma the results and ability to cooperate improve after each round of conversation and negotiation. The level of trust increases and the relationships strengthen; the process is one that builds off of itself to create improved cooperation each time. The evidence of the various international organizations and agreements suggest that this process of the prisoner’s dilemma is currently taking place. Realism is perhaps a more appropriate response when dealing with the consequences of climate change, while liberalism is better suited to create insights in how nations are attempting to solve climate change through international relations.

Work Cited:

Bova, Russell. How the world works a brief survey of international relations. New York: Pearson Longman, 2010. Print.

Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell. Governing climate change. London: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Held, David, Charles Roger, and Eva-Maria Nag. Climate governance in the developing world. Cambridge: Policy Press, 2013. Print.