The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance (CCBA) is a transnational network involved in climate change governance through an intersectional approach involving a diverse range of actors. Conservation International and a collection of five non-governmental organizations comprising its membership, including CARE and the Rainforest Alliance, founded the network in 2003.[i] In addition to these members the CCBA has an advising group of international research institutions (three in total, including the World Agroforestry Center) and the donors to the network (including philanthropic foundations and corporations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and British Petroleum).[ii],[iii] The goal of this alliance is to validate and verify projects that attempt to mitigate climate change through land management while positively serving the native population of that area, from the project’s conception throughout its implementation.[iv] CCBA does this through creating a set of Climate Community and Biodiversity (CCB) standards that generates reliable carbon credits. The CCBA acts as a transnational governing force rather effectively by setting a reputable and premium standard to assist in the regulation of the global carbon market.

In the international climate change discussion, ideas of equity and justice are often raised, and so is the case when discussing issues of land use. The way land is used has huge implications for global climate change; it can be a large contributing factor to emissions through activities such as deforestation or can aid in mitigation through activities such as conservation of biodiversity. Plans of mitigation through “carbon forestry” raised concerns that these projects would inevitably be unjust to native communities because of the high potential of consequences such as displacement of communities.[v] The foundation of CCBA and the CCB standards was to address these concerns in a meaningful way. The creation of CCBA dealt with this issue by not only creating a set of standards that would prohibit adverse effects of land use mitigation projects on native peoples but would also promote and require positive gains or, “co-benefits” for both the community and the environment in projects they validated.[vi]

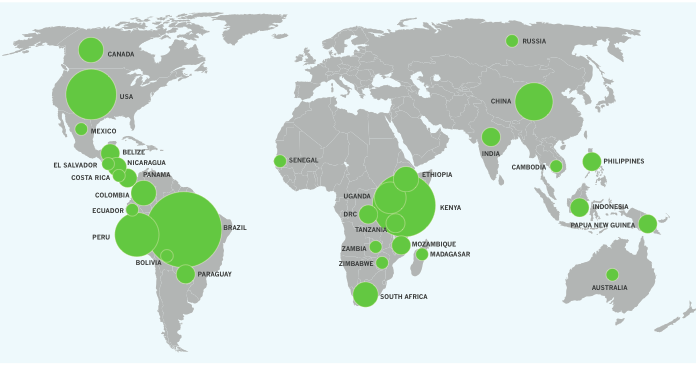

The CCBA is able to promote and instigate these net positive projects through its CCB label. This is a process that involves a certification of “validation” that is an acknowledgment that the project has been heavily analyzed, reviewed and decidedly fulfills the CCB standards.[vii] Validation builds support for the project that then makes implementation and success of the project more likely. After a project has been validated it is then “verified,” which enforces accountability to follow through on promises for co-benefits.[viii] When carbon credits have the CCB label, it signifies they have passed validation and verification and is a high quality credit to the buyer.[ix] A study by the Ecosystem Marketplace’s State of the Forest Carbon Market showed that the investors and offset buyers were more likely to pay extra for the CCB label due to its multilateral approach and diverse range of benefits.[x] This positive reputation has gone hand in hard with increasing number of projects voluntarily seeking approval of CCB standards. In 2010 there were 19 validated projects and 21 in the process, however, over the course of the next three years there 70 projects total were validated, 19 undergoing validation, and 12 projects receiving the CCB label.[xi],[xii] The success of this process of transnational governance is illustrated by the estimated 8 million hectares of land conserved, 180,000 hectares of land restored, totaling roughly 40 million tons of CO2 emissions sequestered.[xiii] Presently, the number of CCB standards approved projects is, in the global picture, minimal. However, the fact these numbers have been increasing rapidly over the past few years eludes to a growing capacity of governing global climate change

Overall, the Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance and the resulting standards appears to be quite effective in achieving its goal of filling a governance function to regulate land use projects that claim to be equitable to communities, have net positive mitigation benefits for the climate and increase the biodiversity and ecology of the land. It has done so by establishing its network and certifications as a reputable marker of governance through its enforcement of accountability and transparency, while engaging market based solutions to global climate change.

This video is an example of the types of projects CCBA deals with.

[youtube_sc url=”http://vimeo.com/31433182″ title=”Conserving%20Rainforests%20and%20Sustaining%20Indigenous%20Communities:%20The%20Story%20of%20the%20Peñablanca%20Sustainable%20Reforestation%20Project”]

Work Cited:

“About the CCBA” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. http://www.climate-standards.org/about-ccba/

Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell. Governing climate change. London: Routledge, 2010. Print.

“CCBA Fact Sheet” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. https://s3.amazonaws.com/CCBA/CCB_Standards_FactSheet.pdf

“CCBA Standards.” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. http://www.climate-standards.org/ccb-standards/

Melo, Isabel, Esther Turnhout, and Bas Arts. “Integrating multiple benefits in market-based climate mitigation schemes: The case of the Climate, Community and Biodiversity certification scheme.” Environmental Science & Policy 35 (2014): 49-56. Web.

Wood, Rachel Godfrey. Carbon finance and pro-poor co-benefits: the gold standard and climate, community and biodiversity standards. London: Sustainable Markets Group, International Institute for Environment and Development, 2011. Web.

[i] Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell. Governing climate change. London: Routledge, 2010. Print. Pg 65.

[ii] Bulkeley, Harriet, and Peter Newell.

[iii] “About the CCBA” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. http://www.climate-standards.org/about-ccba/

[iv] “CCBA Standards.” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. http://www.climate-standards.org/ccb-standards/

[v] Wood, Rachel Godfrey. Carbon finance and pro-poor co-benefits: the gold standard and climate, community and biodiversity standards. London: Sustainable Markets Group, International Institute for Environment and Development, 2011. Web.

[vi] Wood, Rachel Godfrey.

[vii] “CCBA Standards.”

[viii] “CCBA Standards.”

[ix] “CCBA Fact Sheet” CCBA: The Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Sept. 2014. https://s3.amazonaws.com/CCBA/CCB_Standards_FactSheet.pdf

[x] “CCBA Fact Sheet”

[xi] Wood, Rachel Godfrey.

[xii] “CCBA Fact Sheet”

[xiii] “CCBA Fact Sheet”