Critical Approaches and Literary Methods

* * * * * * * * * * * *

English 220 Critical Approaches and Literary Methods Nichols

REQUIRED TEXTS

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre: Case Studies. Ed. Beth Newman. Bedford.

Heaney, Seamus. Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966-1996. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Murfin, Ross and Supryia Ray, The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. Bedford.

Mayes, Frances. The Discovery of Poetry. Harcourt.

Rhys, Jean. The Wide Sargasso Sea. Norton.

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest: Case Studies. Ed. Gerald Graff. Bedford.

(You must have copies of all of these texts in these precise editions)

COURSE AIMS AND LEARNING GOALS:

This course is designed to introduce you to the variety of questions we can ask about literary texts, their authors, and their audiences. We will study a limited number of texts using a variety of critical approaches: formal, generic, reader-response, feminist, psychological, economic, ecocritical. The course will also provide closely supervised instruction in the format and basic elements of critical writing (this is a “W” course). You will be able to prepare a close reading of a literary text, a literary analysis from a stated critical approach, and you will be able to assess the strengths and weaknesses of more than one critical approach in The course is designed to prepare you for the sorts of questions you will be expected to ask and answer throughout an English major, but it is not only for future English majors. The course is designed to help you to explore your own reasons for reading, writing about, and interpreting literary texts in a variety of ways.

COURSE REQUIREMENTS:

Student participation will be a key element of this course. The small size of the class will allow us to conduct our class work on the seminar model, with students providing regular input into class discussion and in-class exercises, both written and oral. More than three (3) unexcused absences will be grounds for lowering your grade in the course. The College’s plagiarism policy will be strictly enforced. If you have questions about plagiarism, contact me directly. You must complete all of the assigned work in order to receive credit for the course. Grading is based on the following scale:

Class Essay #1 Essay #2 Essay #3 Take-Home Final

Participation (poem) (novel) (play) Exam

10% 20% 20% 20% 30% = 100%

Please do not hesitate to contact me at any time during the semester to discuss the course, our readings, your writing, or your grade.

ASSIGNED READINGS AND CLASS WORK:

This class will be unlike others you have had in the English Department. There will be a range of readings assigned for each day, and you will often be asked to emphasize some aspect of those readings for class work. Essays and written work will draw on your reading of all assigned material. You will revise and resubmit almost all of your writing. You will also be encouraged to read more widely than the required reading in order to fulfill the requirements and goals for the course. You will be placed in discussion groups that will regularly be asked to present specific material or questions to the class. The terms listed under the readings below will be defined progressively. You will familiarize yourself with the attached handout on “Interpretive Methods” and be able to refer to and critique these approaches as the semester proceeds. Our class will become more flexible and discussion oriented as our work progresses.

Date Text/s Critical Terms/Method Readings Writing

JANUARY 22 T Our syllabus—Our syllabus as a Text—-Our class as a Dialogue “Read” what?

25 F Heaney: 3-7 Mayes ix-xviii and 1-24, Glossary: “form,” “formalism”

_____________________________________________________________________________

29 T Heaney: 10-11, 13-14 Mayes 25-48, Glossary: “intentional fallacy”

FEBRUARY 1 F Heaney: 29-35 Mayes 66-85, Glossary: “affective fallacy”

_____________________________________________________________________________

5 T Heaney: 100-114 Mayes 85-108, Glossary: “irony,” “paradox”

8 F Mayes 138-155 ————Imagine one image

_____________________________________________________________________________

12 T Heaney: 156-165 Mayes 165-184, Glossary: “New Criticism,” “genre”

15 F Heaney: 72, 120 Mayes 184-201

_____________________________________________________________________________

19 T Mayes 217-232 (“Ozymandias” handout) Workshop Draft of Essay #1

22 F Heaney: 214-17, 332-41 Mayes 232-45, Glossary: “poetry,” “poetic diction”

______________________________________________________________________________

26 T Heaney: 411 ESSAY #1 DUE

MARCH 1 F Brontë: 15-220

______________________________________________________________________________

5 T Brontë: 220-441

8 F Film versions of Jane Eyre

______________________________________________________________________________

12 T SPRING BREAK

15 F SPRING BREAK

______________________________________________________________________________

19 T Brontë: 445-459 Glossary: “new historicism” “ecocriticism”

22 F NO CLASS Novel reading day ______________________________________________________________________________

26 T Brontë: 459-633 Glossary: “feminist criticism” “reader-response criticism”

29 F Rhys: 17-61 ————————-Workshop Essay #2 Draft

______________________________________________________________________________

APRIL 2 T Rhys 65-190 Glossary: “Marxist Criticism”

5 F NO CLASS Research Day for Essay #2

______________________________________________________________________________

9 T What is a Novel? Glossary: “novel” ————————————-ESSAY #2 Due

12 F Shakespeare Act I-II

______________________________________________________________________________

16 T Shakespeare Act III-IV

19 F Shakespeare Act V

______________________________________________________________________________

23 T Shakespeare 91-116, 246-254 Glossary: “gender criticism,” “feminist criticism”

26 F Shakespeare 203-229, 255-268, 323-349, Glossary: “poststructuralism,” “postcolonial”

______________________________________________________________________________

30 T Exam writing (favorite Heaney poem, favorite Shakespeare scene)———ESSAY #3 DUE

MAY 3 F Last Class and Discussion of Take-Home Final Exam (Class evaluation)

______________________________________________________________________________

Monday, May 13, 12 noon (NO LATE EXAMS): Take home final due in KAUFMAN 192

______________________________________________________________________________

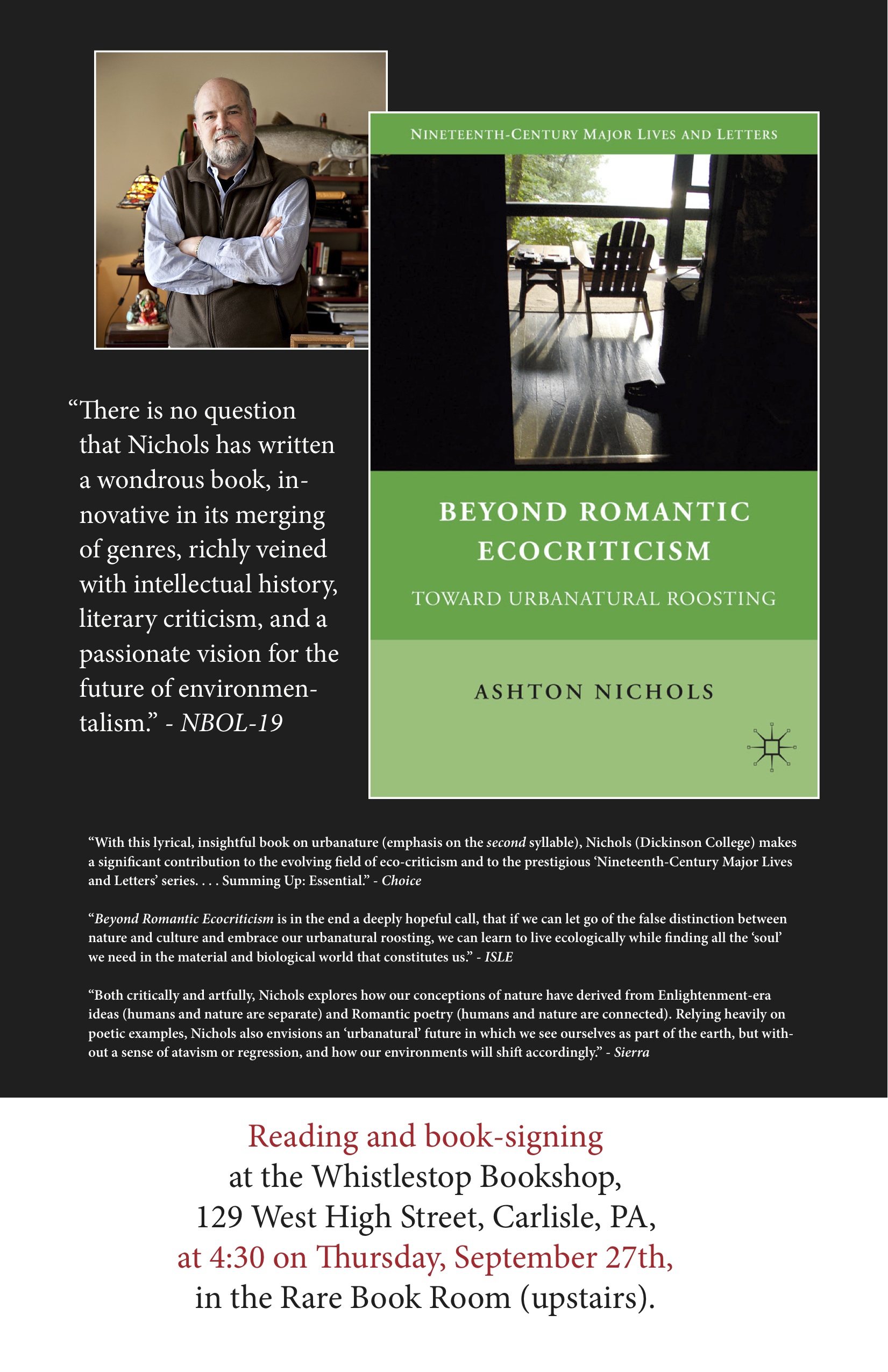

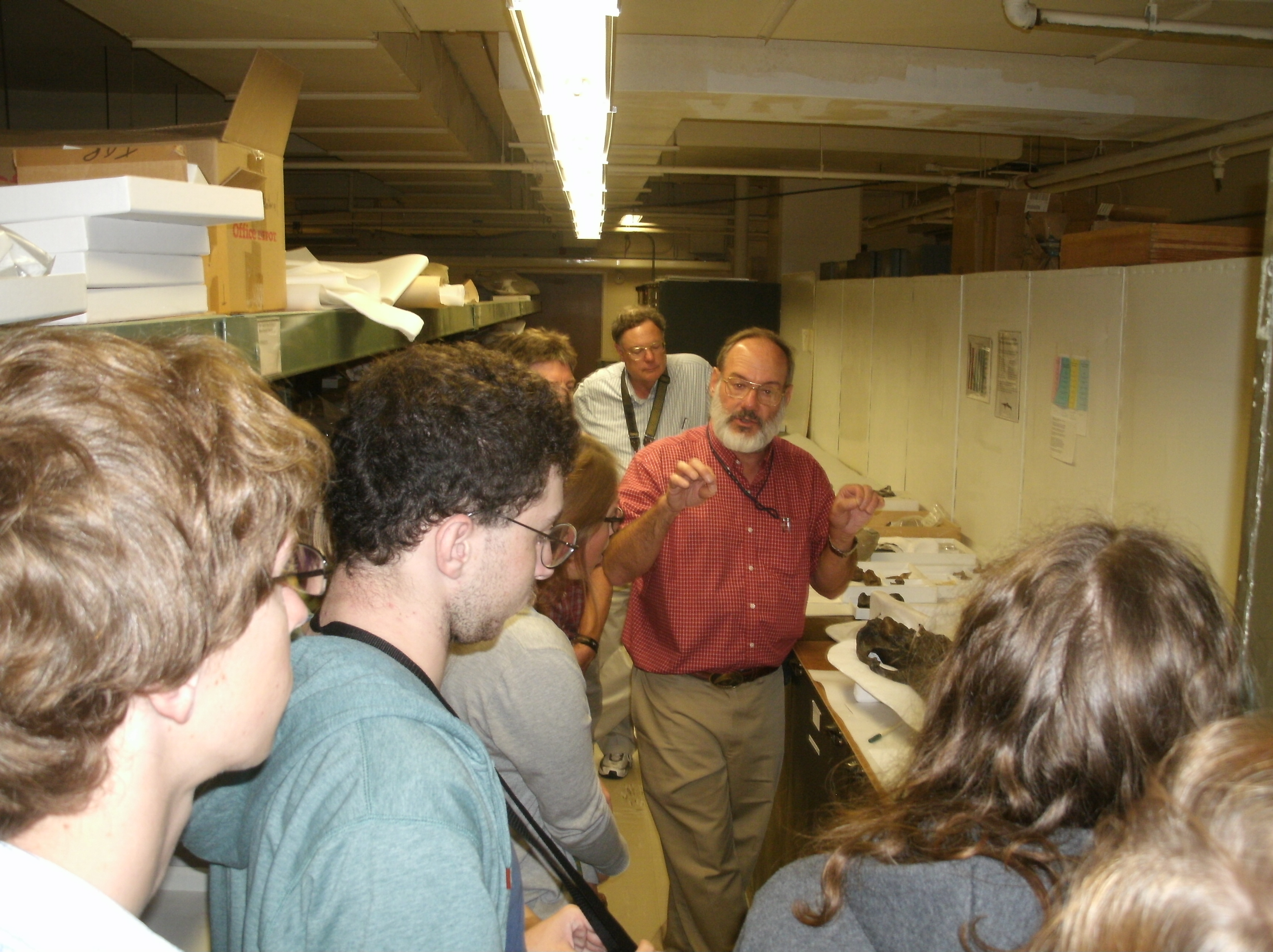

Professor Ashton Nichols, Class 1:30-2:45 p.m, T & F, Kaufman 178

Office Hours: W 2-4 p.m., F 10 a.m.-12 noon (and by appointment)

Academic Honesty

The Dickinson plagiarism policy will be strictly enforced. This class adheres to the college’s Community Standards, which clearly state: “Students are expected to do their own work. Work submitted in fulfillment of academic assignments and provided on examinations is expected to be original by the student submitting it.” Please review the Community Standards document for more information. Please do not hesitate to ask me any questions you may have about citation, documentation, or academic honesty.

Statement on Disability Services

In compliance with the Dickinson College policy and equal access laws, I am available to discuss requests made by students with disabilities for academic accommodations. Such requests must be verified in advance by the Coordinator of Disability Services who will provide a signed copy of an accommodation letter, which must be presented to me prior to any accommodations being offered. Requests for academic accommodations should be made during the first three weeks of the semester (except for unusual circumstances) so that timely and appropriate arrangements can be made.

Students requesting accommodations are required to register with Disability Services, located in Academic Advising, first floor of Biddle House. Please contact Marni Jones, Coordinator of Disability Services (at ext. 1080 or jonesmar@dickinson.edu ) to verify their eligibility for reasonable and appropriate accommodations.

Interpretive Methods: A Primer for 220

Critical approaches are not cookie-cutters placed over a text. Effective interpretations draw on more than one approach in order to develop an argument. Every one of the categories below overlaps with others in important ways. Less useful interpretations force the text into narrowly methodological readings; such reductive interpretations always weaken an argument by leaving it open to objections from other points of view. The following categories, however, represent ways that literary critics and theorists have been talking about texts for the past half-century. Your own reading and writing about literature should reflect the ways that you give emphasis to various sorts of questions that can be asked about texts.

Textual (Philological): this form of analysis emphasizes the physical text as an object of study. Is there still a manuscript copy of the work in the author’s handwriting? Are there conflicting manuscript versions? Can we date this work? How? How did the author or editor revise the work over time and in different editions? How might these questions influence our understanding of the text?

New Critical: a form of reading that stresses our ability to analyze a literary text without considering the circumstances surrounding its production. Such reading de-emphasizes the author and the historical context in favor of a “pure” analysis of language as language: tropes, symbols, metaphors, allusions, metrics, narrative structure. A “great” work is then seen as one that exemplifies certain identifiable characteristics: unity, complexity, subtlety, allusiveness. Sometimes identified with “close” reading.

Historicist/New Historicist: traditional forms of historicism emphasize the importance of historical “background” to the understanding of literature. The more a reader knows about the time and place in which a work was produced, the more effective will be that reader’s interpretations of the text. So-called “new” historicism argues that history itself is much less stable than we thought because our understanding of the past is always conditioned by our mediator (the historian) and by our own subjective position in a complex, multivalent culture.

Biographical: reading that emphasizes the author as a key to understanding the text. Such interpretations see the author’s childhood, education, family background, social class, and life experiences as important critical considerations. Traditional biographical readings tend to see authors as “products” of their times. More recent authorial critiques tend to stress the psychology of the author as a key to literary interpretation. Did the author long for a “mother”? Did the author hate a “father”? What did the author hide? Do we identify with the author’s life?

Psychological (Freudian): such readings see psychological categories and terms–conscious, subconscious, ego, id, superego, Oedipal, repression, transference–as important ways of talking about literature. They may focus on the psychology of the author, the characters/voices in the text, or the reader, seeking to explain plots, imagery, and authorial intention in terms of an analysis of mental events. For such interpretations the “hidden” aspects of a work are often more important than the “obvious.”

Economic (Marxist): Marxist interpretations emphasize the economic and material conditions of all human activity. Such readings claim that literary works are a function of the material circumstances of the author (rich or poor) and the economy of the author’s society (feudal, mercantile, capitalist, socialist). Such readings also stress the role of literature in hiding or revealing class distinctions and the need for political change.

Reception/Reader Response: discussions of responses produced by a text on its audience. Such critiques might discuss acceptance or rejection of a work by the reading public over time, reception by contemporary critics, or the current state of criticism of a text. Reception theory also analyzes and interprets the process of reading itself? What does it mean to “read” a work? What does it mean to “misread” the same work? Could we read disinterestedly?

Deconstructive: de(con)structive readings set out to reveal the linguistic tensions in a literary text. They also want to argue that all language is less st(able) than we often assume. Does “light” always imply, contain, or implicate “dark”? Does a seemingly unified text contain contradictions? How might a poem about the beauty of nature actually reveal the author’s own confusions about his pre/con/re-ceptions. Do certain words hide a much as they reveal? Do we find “true” meaning or make our own meanings? Is there “Meaning,” or are they only “meanings”?

Feminist: such readings stress the fact that women and men have different sorts of experiences–including linguistic experiences–or point out similarities across gender boundaries. Feminist interpretations might draw attention to the fact that the author was male or female, or to varying responses by male and female readers. Such readings also tend to emphasize the history of gender relationships as a key to understanding the text. At the most theoretical level a feminist reading argues that language itself is male or female (i.e. based on certain gendered assumptions).

Cultural Studies: a form of criticism that sees literary works not as the products of “genius” authors, but rather as artifacts of the cultures in which they were produced and in which they are interpreted. Cultural studies also incorporates the records of societies–imaged, photographs, films, clothing, objects–into the concept of “text,” arguing that to read a text is to read the culture in which it was produced and also the culture in which readers are performing the act of interpretation.

Ecocriticism: a recent form of interpretation that has emerged out of emphasis on the relationship between humans and the natural environment. Ecocritics emphasize the role played by nonhuman nature in a wide range of literary texts. They also interrogate the ways that human interactions with nature (plants, animals, geology, landscapes) have affected human life and the natural world. Many ecocritics have environmentalist or preservationist agendas; others are more interested in the philosophical and cultural implications of human understanding of and impact on the natural environment.