“the best rails in the world!”

Past & Present

THE STEEL MILL OF THE PAST

When the newly-formed Pennsylvania Steel Company was brainstorming for the location of the first American steel plant in 1866, they decided on an area about three miles south of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. It was an excellent location. Besides the fact that there was a large amount of coal in Pennsylvania, this area also neighbored the Susquehanna River, a canal, and a main line of railroad. The company bought 97 acres in this area.

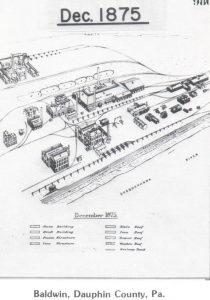

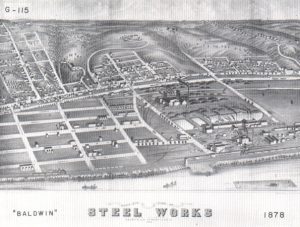

On May 12, 1866, Pennsylvania Steel began building the plant in Baldwin, the original name Steelton. The company gave the first jobs to English and Irish immigrant workers who had experience using the Bessemer Process. Almost exactly a year later, the first steel product–an ingot for rails–was manufactured and sent to Johnston, PA, where the rails were sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad, setting the record as the first rails made in America for commercial sale. The mill itself began making rails in 1868, becoming the first facility in the United States with the main purpose for making steel. Pennsylvania Steel Company also built the largest steam hammer for the forge shop at that time in the United States. The mill also installed the first iron-producing Open Hearth Plant and Blooming Shop in the 1870s. During this period, the company also constructed houses for the steelworkers. The picture below on the left is a sketch of Baldwin in December of 1875. As you can see, most of the town consisted of the steel mill, with only a few houses surrounding it. By 1878, as shown in the picture on the right, the planners quickly expanded the town and gave it a new name. It was temporarily “Steel Works” until they established the borough and post office in 1880, when they changed the name to “Steelton.”

- A sketch of Baldwin in 1875 Image from Stop, Look, Listen: Steelton, Pennsylvania

- A sketch of Steel Works in 1878 Image from Stop, Look, Listen: Steelton, Pennsylvania

The reputation of the Pennsylvania Steel Company quickly grew, allowing the company to expand its facility. They replaced many parts of the mill with state-of-the-art equipment, such as two twenty-ton furnaces, which abled the company to work more efficiently, and lowered the cost of manufacture. Shortly before 1881, the company again needed to improve its manufacturing output, so the managers added a second Bessemer Plant. They prided themselves by making most of the new equipment, such as the boilers and engines, in the plant. Early after its construction, the new facility was able to produce over 800 tons of steel in one day.

As a result of a strike in 1891, the company was forced to close the mill for the first time for protection measure. Shortly after the strike ended, the company recruited many southern European immigrants to work at the mill. As more nationalities came into the mill, each ethnicity occupied specific kinds and sites of work. For example, the skilled-labor positions were given to the Germans, Irish and Italians and the blast furnace jobs were assigned to the southern Europeans and African American southerners.

The 1907-1908 Depression hit Steelton hard. More than half of the Bulgarians and about a third of the Serbs, Croats, and Italians left in order to find employment either somewhere else in America or back in their homeland. Two years later, in1910, the economy for the steel industry began to get better, resulting in the return of many workers and their families. In fact, 1910 was so prosperous for Pennsylvania Steel Company that the Steelton facility doubled its net profit from 1880 and Steelton’s population reached an all-time high at 14,246.

On July 7, 1917, Pennsylvania Steel Company announced it had sold the Steelton facility to Bethlehem Steel. The population dropped to about 13,000 in the 1920s and stayed there until the Depression. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, many workers were laid off and either moved back to their original homelands or moved to another part of the country. Deacon Ollie Allen explained the sequence from the Depression to the war years,

“Things were really tight at that time, in the thirties, you know. And finally my brother lost his job up there. He had diabetes and he couldn’t hold a job there. But he got down here during the war and he got a job here at Bethlehem Steel. They was hiring anybody then, crippled, blind, or whatever.”

World War II allowed many opportunities and changes within the mill. Mitch Ivanoff, a steelworker and union member, discussed some of the manufacturing:

“At one time, they had what they called a “bridge shop” which makes all of the components to assemble a bridge. They’ll actually assemble it in pieces there, then ship it, and then assemble it on-site. The majority of the parts of the Golden Gate Bridge were made there. We had another part that’s now closed also, called the Steel Foundry. Particularly during the war, they cast steel there. It’s not rolled steel, it’s melted, then casted into molds, then further refined. Propellers for huge battleships, lots of cast parts for the Navy, lot of stuff for the armed forces were made in there, all over the plant during the war. Many women were employed there at the time. In fact, that was probably their highest level of employment.”

After the war, the union started to become powerful. In order for the employees and the company to work together, Bethlehem Steel often made agreements with union. To ensure safety in the mill, the company and union decided it would be best to have the latest equipment and technology within the facility. Mitch Ivanoff describes how the union members often had to compromise in order for the company to purchase the new equipment:

“That is another thing — at times we have given concessions and other times we have given up. Raises and at one time a week of vacation back, a few

holidays, to be able to pay for this technology, to bring it in. As a matter of fact, we’ve paid for, the steel workers union, have paid for all of the new tech we have down there.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Current Steel Facility

2001: The mill only works with recycled steel. The workers roll steel for the railroads and/or redefine the steel for future purposes. Mitch Ivanoff describes what is currently going on in the mill:

“Depending on the specification, what the customer needs, what type of alloy steel it is, steel can be very soft or made very malleable or soft or hard or very brittle. Depending what it needs, that’s what we’ll add to it, things like manganese, silica, particularly carbon, the carbon when we get to the hardness.”

Later, he goes into the mill’s current status in America’s industrialized market:

“Right now in the plant, we have a very soft market. It’s been going on for the past two years. Imports have affected the domestic steel industry, not just Bethlehem Steel, but all of the steel producers, particularly the what they call an integrated mill like ours, which is a mill that makes steel and further refines it from raw steel to the actual finished product. Right now, as far as rail, there are two rail mills in the United States that supply all the east of the Mississippi and west, of course we do east of the Mississippi and Colorado, what used to be,Colorado Iron and Forge, it’s called Rocky Mountain Steel now in Colorado. They’re our main competitor. We have about each about twenty-percent share of the domestic market and the rest is all imports.”

Below are two images of how the steel mill looks today. The left one is the entrance to the mill. The words on the black structure say “Good work is done safely.” The right picture shows what all is left in the mill: a scrap metal recovery operation.

- The entrance to the mill in 2001 Picture taken from DV video

- The scrap metal recovery facility in 2001 Picture taken from DV video

Stories of the Mill

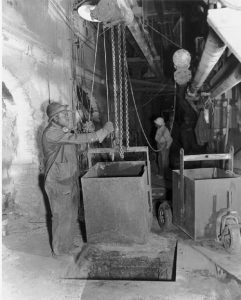

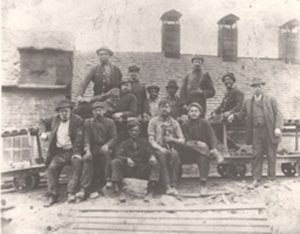

Steelworkers in the early days.

Photograph from the John Yetter Collection,

with permission from the Penn Cultural Center

Many people have stories about how started working in a certain location of the mill, especially on their first day:

“The boy who was working up on the cradles, he worked there about a half-hour, and he didn’t like it too much. He told them he had to take a leak right now; he’d be right back. He went right to the gate, left his work shoes at the gate, and went home and never came back. So, I got promoted at the cradle. And that’s when the guys asked me to go out with them. They asked if I wanted to go stop with them. That was my first night out drinking with the boys at the age of nineteen. We went to The Roma that night. It was really neat. Just about the whole turn went, everybody went, even our boss Big John was with us.” — Mitch Ivanoff, a steelworker and Chairman of the Safety Committee

“With all the apprentices I ever had, I taught them the machinist trade. If they were nice to you, you taught them. If they weren’t nice to you, you let them sit.” — Harold Kerns

“I worked in the eleven-inch bar mill until it closed. I worked there seventeen years, from ’71 to ’86. It closed in February 14th, 1986. We referred to it lovingly as the “Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre” because the guys in there were so close that it was very traumatic when they shut it down. It was real hard to take. While I was in there, I learned to do many jobs. Probably one of my favorite jobs was running that big football-field-size machine, that big cooling bed that you actually lay the steel. A lot of adjustments and a lot of coordination and I enjoyed the challenge of it. Because one miscalculation, although we had a logic system controlling it, it was totally controlled by the person operating it. You know, a little mistake and you’d have red hot steel all over the place.” — Mitch Ivanoff

A common fact we heard in many of the interviews was:

“The Golden Gate Bridge, more than twenty percent of it was built in Steelton.” — Frank Albert

“The Stovermill Bridge was built in 1868. The plant was only started in 1866. So, two years later, they built this and this could be one of the first projects ever made out of the bridge shop. Right here. Only two years after the plant was built. And they were busy putting the rail mill and everything else in. So, this might be the first project they ever did.” — Harold Kerns

Different races often had certain jobs in the mill. For example, Deacon Ollie Allen listed a few places where blacks did not work and explained the crossing of those borders:

“Well, the blast furnace I guess would be one, what we’d call a smoke tender, and crane operators and so forth. I was the second one that they put on the “larry” cars during the time. One man was already on there so, and then I went on, but it’s a lot of funny things that happened during that time ’cause I trained a white fella that came in…He had a long twisted mustached, he kept twistin’ his mustache and lookin’ at me. He thought I was gonna start a fight or something… and the poor fella quit. He couldn’t stand to look at me no more. He went up and got his clothes and left. I felt sorry for him…but, you know, I guess we made it.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Health and Safety in the Mill

Safety and health regulations at the mill increased with time. Some of the retired steelworkers that we interviewed talked about the changes in the mill. This excerpt is from Deacon Ollie Allen: he explains some of the gear they wore:

“When I started workin’ we didn’t wear helmets, you know, but then they, they’d be required, we had to wear these, these hard hats, and when you around dust you had put, put this mask on and you must wear eye goggles. Now that was a great help because a lot of people got this um, down at the foundry, they got this steel dust in their lungs and they send them up to Mount Alto and they said they had T.B. (Tuberculosis),but they didn’t have T.B. it was the lung was eaten up

with the steel particles.”

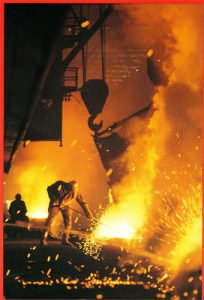

A picture of the Blast Furnaces in 1926,

showing the dust particles in the air

Photograph from Stop, Look, Listen: Steelton, Pennsylvania

When asked what was the dirtiest job at the mill, several steelworkers mentioned the “larry cars.” They were the train cars that unloaded the coal to fuel the furnaces. The workers stationed there unloaded the materials and put them in a “skip” which carries it into the furnaces. During the tedious process of unloading, a lot of dust particles were constantly in the surrounding air which they breathed. It also involved a great deal of hard labor. Deacon Ollie Allen explained his job at the “larry cars” in this short section of transcript:

DA: “I was trained on a what they call a “larry car” and carrying ore and stuff to the furnace, blast furnace. And that’s where I worked until I went into the service. When I got out I got the same job back again. And I moved up a little when I got on what they call a “skip,” what carries the stuff up into the furnace, so I was there for about five years, that’s when they shut down altogether.”

Mike Weniger, a Mosaic student: “How did you like that job?”

DA: Ahh, well you didn’t know anything else, but–, so, it was all right, it was all right.

There were also certain parts of the mill that were more dangerous than others. Each narrator who discussed this topic shared stories about horrible injuries and deaths that occurred in the facility through the years. Deacon Ollie Allen described a personal injury:

“I went down the pipe shop where they makin’ these big pipes and the crane would pick ’em up in the center and that was it, including the pipe and the pipe went away, banged me against another pipe. I thought I was crushed. I couldn’t speak, the fellas sayin’ “I bet this man is dead, he turned white” and I wanted to tell ’em “No, I’m still livin’, don’t give in yet!” When I really woke up, I heard the ambulance comin’ up through Steelton to the hospital…a couple fellas got killed on the same job I was at. A pipe coming down and they wasn’t lookin’ and just crushed ’em. One fella lived right here in Steelton, and he was killed. Well, a lot of ’em killed…So, I was saved by the mercy of God I guess.”

Mitch Ivanoff was another steelworker who narrated a few injury stories. He explained that many of the men were injured on the job, however, after a while, many seemed to become untouchable. The elder workers were role models, full of bravery and toughness.

“Before I started there…Joe was standing down at the lower end of the cooling bed before they erected the bulkheads (barricades to stop the hot steel traveling at about thirty-five miles an hour), and the arms got twisted up with red-hot steel around them, and you still got steel coming down the roller line. The front end of a 240-foot long red-hot bar went through his calf, and the whole bar wrapped up all around him…If you can imagine this. And he didn’t pass out or anything. They had to cut him out of it, out of all the steel. And, he’s fine. He didn’t lose his leg. He was actually very lucky. It didn’t hit the bone, it just went through the calf muscle, but it instantly stopped bleeding. It cauterized it, you know. The steel was probably, when it hit him, about 1850 Fahrenheit …These kind of guys that have been through these things, you know, when you are a young guy, you look at them like a young guy that might go into the army and view his master sergeant, the guy who really leads him, the guy that inspires him, shows him the way, you know. I feel the same way about them.”

Harold Kerns describes the dust particles in the plant, then Frank Albert adds how the mill operations affected the town:

HK: “They had poor lighting, so they had big windows to let the light in. I’d stand there and as the sun was really shining in them windows, you could see hundreds of particles of dirt in the air, hundreds of particles, thousands of particles all of the time.”

FA: “And the vast part was in town…When I read water meters for the Borough of Steelton, I started in ’42, all of Front Street, the window sills and everything, was all full of orange dust just from that…It was really terrible.”

Later in the interview, they discussed how the West Side was the cleanest area because the wind usually blew down river. They said from the Blast Furnaces in the center of town to the Lower End, they had problems with orange and black dust. People would put their clothing out to dry and soon after, everything had a thin orange cover of dust.

*Today, many hazards still exist. The particulates, such as cadmium, lead, aluminum, and chromium can cause several health problems. Some of these include lung disease, ulcers, birth defects, nausea, and even death. Besides the chemicals and metals, some of the other hazards include the loudness, the extreme heat, and high noise levels.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Occupational Safety and Health Act

The Occupation Safety and Health Act (OSHA) was created in 1970. It sets the standards for exposure to hazardous chemicals and the ensurance of safety in the workplace. While it gives the worker and the Union more power, it also demands the government (Department of Labor) to conduct checks in the workplace. It also ensures that MSDS sheets that list the chemicals and safety precautions are posted within the plant. Many environmentalists see OSHA as being weak because the inspector usually gives a two-week notice upon visit and the visits are only once a year, there is chance for legal defense from the company, and it currently only covers 500 hazardous chemicals.

Mitch Ivanoff, the Chairman of the Union Safety Committee, explains his duties under OSHA enforcement:

“If I feel that if people are exposed to hazards, I can request testing, such as air quality or radiation…If they are exposed to hazardous chemicals, we test the air for nine metals, and also lead. I am there to make sure the company follows every part of OSHA. It covers just about everything that needs to be looked at as far as people’s safety from simple, guarding of machines where people can get wrapped up in things, how you can guard people from that, to protection from falls when working on heights and working in trenches, working in what they call confined spaces– which is an area which is not normally inhabited by people– in other words, if you were in a vessel or a tank or a, because of the possibility of being engulfed in a hazardous atmosphere. OSHA regulates many things and I feel it’s up to me to make sure that the company complies with those regulations.”

~~~~~~~~~~

The United Steelworkers of America

Even though the “Roaring Twenties” was economically successful for most big businesses in the United States, the majority of the steel labor force continued to be unorganized. In 1935, during the devastating Great Depression of 1929-1941, newly elected Franklin D. Roosevelt helped pass the National Labor Relations Act. It was the first government act that allowed workers to bargain for their protection against working conditions, ask for higher wages, and have more control over their hours. The major step in unionization was also in 1935 when the Committee of Industrial Organization (CIO) was formed. In 1942, already with over 700,000 members, the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) was officially formed. More than a decade later in 1959, the USWA held its longest strike in history, setting the record with 116 days. With successes throughout its history, the USWA came up with an important plan in 1965. The agreement called for higher wages and an improved pension plan. Today, with over 700,000 members, the USWA is worried because the steel industry is low in demand. At the end of 2000, the industry operated less than 65% of its capacity. The USWA is calling for a Steel Revitalization Act to ensure the international market demand for steel will increase and that the mills stay open. This information was taken from the USW website.

Mitch Ivanoff discussed the importance of the Union:

“It protects everybody, it saves the company money, it keeps the lives of my brothers and sisters in the union as unaffected by their work as can be. I mean, when people are hurt in industrial accidents, they’re generally very severe. We just had two fatalities and three criticals at our Bird’s Harbor Plant, Indiana. Just a freak thing, the, two men burned alive, and three more burned very critically. They usually don’t live very long after bad burns like that. It’s super-heated air in your lungs and it’s just a matter of time.”

For more information on current environmental information of the Steelton facility, such as amounts of chemicals used and released, go to the Right-To-Know Network.

For more information on the steel mill, please visit the Mosaic 1996 page.