“You had to see it to believe it.”

–William Pettigrew, Jr.

The Canal along the West Side

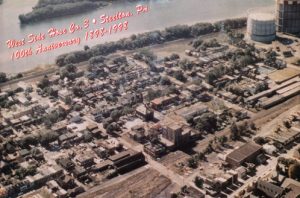

Photograph from Stop, Look, Listen: Steelton, Pennsylvania

In the early 1870s, a Harrisburg ealty firm bought from the landowner Walter A. Trevoich a small piece of land next to a new steel company located between Front Street and the Susquehanna River. Shortly after the sale, the formation of a town began. In 1875, Purdy and Ewing named the area Ewington, but eventually, it was simply known as “Steelton’s West Side.” Little did everyone know that later in its history, the area would experience relatively harmonious racial and ethinic relationships, decades of steel making, several devastating floods, and eventually the demolition of all its buildings.

Some of the first residents of Baldwin lived in the company houses located in “Furnace Row” near Locust Street in Ewington. They were immigrants from a variety of countries, and included Germans, Irish, Jews, Slovenians, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Croatians, and African-Americans. Despite their differences, they shared one common goal: they all came to find work at the steel mill.

Ewington quickly developed into its own enclave, eventually containing its own churches, schools, hose company, hotel, lumber and coal yards, grocery stores, flour mill, and even a brewery. Even after the village was annexed to the Borough of Baldwin on March 25, 1882, it remained as its own entity. The West Side School, located at 315 Main Street, was one of the first schools built. Two years later, due to over-crowded conditions, the Major Bent School was erected. Both photographs below are from Stop, Look, Listen: Steelton, Pennsylvania.

- West Side School

- Major Bent School

In 1889, the ‘Great Flood’ hit Steelton, covering most of the West Side and the steel mill with more than ten feet of water. Fortunately, most of the residents were able to find shelter and food from other neighbors and churches in Steelton. It took a long time afterward for the town, especially the West Side, had to rebuild from its losses. This was a similar consequence for the ’36 and ’72 Floods as well.

Throughout its history, the West Side was a town within itself. It had its own grocery stores, ice skating rink, baseball fields and basketball courts, schools, and job opportunities (besides the steel mill). Some Steelton residents claim that non-West-Siders wished they lived in the West Side. It was known as being extremely diverse, with all of the ethnicities living door-to-door with one another.

The West Side before it was demolished

Life In the West Side

Sports

“We had a big ball field where we played our football and our baseball. We had one basketball court which a lot of people came to from the Lower End of Steelton. People from Harrisburg even came down, we had people from all over come just to play ball. Hitting the ball over the top of the building, homerun derby, did a lot of things over there. They had swings, they had merry-go-rounds, they had, but it was all on concrete, it was all stones. You know, so, glass, if we didn’t clean it up, nobody did.” –William Pettigrew, Jr., steel worker

“It was easy to have enough people [for a game]. The hard part was coming up with nine gloves.” — Joe Conjar, a Steelton police officer

“When we were poor, we didn’t know we were poor, and I used to be the catcher of our softball team of fast pitch. We had a ball and a bat, nothing else. And I used to catch barehanded. And the eye doctor and I figured out that all them foul tips were what jarred my eye here in ’49, I had to get a cataract removed because of it.” — Harold Kerns, retired machinist and local historian

“We had our East Side verses West Side baseball games, basketball games, or street football. We even used to have races. We used to go to the cemetery which is at the top of the Steelton Mill and have races, relay races. We used to go down there and play down there, you know, five guys or ten, eleven guys, whatever sport we were playing, we’d say, ‘Let’s go down to the Lower End and see if we can pick-up, find some guys to play baseball.’ And we used to find them. And, they’d be on! We’d be on. It was pretty interesting.” –William Pettigrew, Jr

Tough Times

“Everybody helped each other. If there was a death and you didn’t have insurance, people were there to help you.” — Teresa Ward, owner of Tree’s Tavern on Front Street in Steelton

“We’d eat things that these kids today wouldn’t even touch. Oh yes. Did you ever eat brown-floured beans? Did you ever eat brown-floured potato soup? No, I know you didn’t. Did you ever eat toast bread with lard on it, put salt and pepper on it to have something to eat? I am talking way back. Now, I was living and he (Harold Kerns, a life-long West Side friend) was living during the Depression. I was just a young boy, but I remember. We struggled. Some guys couldn’t take it, so one guy blew himself up in the quarry. This wasn’t just Steelton though. It was all over.” — Frank Albert, retired Borough employee

“I think that we was one of the first black families on the West Side to even own a TV. Everybody used to come to our house to watch TV. –William Pettigrew, Jr.

“My father worked in the steel mill when he was a young boy. He worked thirteen-hour day times (during his turn of day work)) and eleven hours at night (during his night turns). He told me he was getting thirteen cents an hour…That was a lot of money. Of course, you could pay rent on the house. Some of them were $3.00 or $4.00 a month for rent, but you didn’t have a lot to eat. You had to sacrifice all of the time. It was makeshift food and stuff. We went through some tough times.” — Frank Albert

“See a lot of death over there. Some people trying to beat the trains across the railroad tracks.” — William Pettigrew, Jr.

Childhood Memories

“There was a lot more kids over there than anybody wanted to see, I’ll tell you that. We all stayed over there. You had everything you needed and you ain’t never had to leave the West Side. We lived on that other side of the tracks, of course we had a lot of water over there. Five times I was in water.” — Robert Phillips, retired state employee and long-time resident of Steelton

“In fifth grade, we had one boy who smoked. That was a rarity when I was a kid. His name was William Esterby; they called him “Buck.” So, Mrs. Brown [the teacher] was a fine woman and she said, “Put your hand up if you got to go to the bathroom. [Looking at Buck] You’re not going to the bathroom. I’ve just been told that you smoke. And that’s illegal. You dare not smoke. It’s a fire hazard and you are not allowed to smoke.” She wouldn’t let him go. He kept putting his hand up.

She got mad and locked him in her personal clothes closet. So, when she dismissed her class in the afternoon, she went and got him and gave him a lecture and when she went to put her clothes on, he did his business in her hat.” — Harold Kerns

“Whenever winter would come, [the West Side Hose Company] would ask permission from the Borough to hook up to a hydrant and they would spray water and then they would pour another layer on. Hundreds of people from Middletown, Paxton, from all over the place would come to ice skate. In the summer time, they would put water in there…We used to dive off of there and I had belly-floppers, my chest and everything.They used to have marble-shooting contests and paddleball and a lot of that was down at the West Side Hose Company Rink. They had Santa Claus, they had Easter Bunny, they had movies for a quarter a piece for kids. They had dances for them. Really, if there was ever a community center in the world, that was one of them.” — Frank Albert

“Them people over there were all West Siders. That was it. There wasn’t no black or white, Irish, Hunkies, or whatever you call ’em.” — Robert Phillips

“They had seven places on the West Side where they baked bread…One was called Vienna Bakery, it was on Mair Street. They made donuts and cakes and stuff like that. Now, the other one, the Balkan Bakery, they had loaves of bread, how ’bout it Harold, oh man! It was delicious. [The owner of a particular bakery] knew we used to sneak some when we were kids. He had racks in there with hundred and hundreds of loaves. He’d stick two or three in the windowsill because he knew us kids would get it and eat it.” — Frank Albert

~~~~~~~

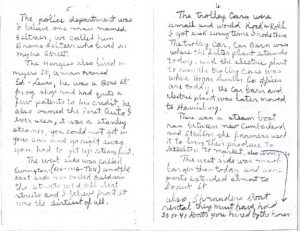

*Harold Kern’s father, Clarence Kerns, wrote several journal entries about life in the early 1900s. Here are a couple of excerpts. The writing image below is a page from his journal.

“My dad and many more dads could not afford to buy coal, so us kids picked coke from the steel company dumps for winter and summer use as all coal stoves were used those days.” — Clarence Kerns

“We also got up early about two days a week and stirred old fashioned hand washers before we went to school.” — Clarence Kerns

A journal entry of Clarence L. Kerns

After the ’72 Flood ruined many of the structures in the West Side, the federal government came to Steelton and decided it was not safe for residents to continue to live in the West Side section of town due to its proximity of the Susquehanna River. The government forced about 2,000 West Side residents to leave their homes. Many of the residents who wanted to stay in Steelton could not find another house in the town, so they had to find residency somewhere else. After the town was abandoned, the government demolished 452 houses. Today, the area is a part of a scrap metal recovery plant and the UGI Water Facility.

Joe Conjar, a Steelton police officer, told us how he remembers the situation:

“[Federal government] told the local government that, ‘We will come in here one time and aid you. And if you don’t relocate, you won’t be able to get homeowners insurance or flood insurance. It was a one-time federal aid deal and that was it.”

The demolition of the West Side in 1972

“If they was to build houses back over there again I think a lot of people would move back over to the West Side. I think a lot of people who were former West Siders would move back.” –William Pettigrew, Jr.

“This is really a drop in the bucket. You could spend weeks just talking about West Side. How ’bout it, Harold? Weeks and weeks and weeks. See, they had a pump and it was called Shaeffer’s, remember, Harold?…” — Frank Albert

*I would like to thank Harold Kerns, Frank Albert, and William Pettigrew, Jr. for the hours they spent sharing with us all of those precious memories and advice for the future. I will never forget. –E.W.