English 212 * * * * * * * * Professor Nichols

* * * * *

ENGL 212/211

Writing About Nature

Spring 2015

Required Texts:

Dillard, Annie. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Harper Perennial. 2007.

Fergus, Charles. Wildlife of Pennsylvania. Stackpole Books. 2000.

Hacker, Diana. A Pocket Style Manual 5th edition. Bedford St. Martin’s. 2011.

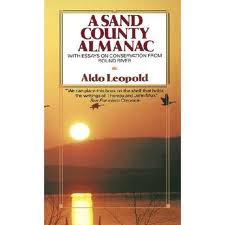

Leopold, Aldo. A Sand County Almanac. Ballantine. 1986.

Nichols, Ashton. Beyond Romantic Ecocriticism: Toward Urbanatural Roosting. Palgrave Macmillan. 2012.

–all in paper, all in these editions

Course Aims and Learning Goals:

This course is designed to improve your skills as a writer of expository prose by emphasizing the genre of nature writing. We will concentrate on a variety of writing problems and techniques, emphasizing specific skills necessary to a wide range of writing tasks: description, narration, analysis, and interpretation. In all cases, our focus will be on the natural–or nonhuman–world and human connections to that world. Discussions of essay reading assignments will be supplemented by workshop sessions and individual tutorials and fieldtrips. Students will have the opportunity to critique one another’s work and to compare their essays to works by nature writers of the past two centuries. The course aims to concentrate your attention on all of the precise stylistic details that can lead to effective writing.

This class will also make use of a new pedagogy–or teaching method–known as “blended learning.” So-called blended learning takes advantage of the multitude of electronic tools and techniques now available, both inside the classroom and out, to assist teachers in teaching and students in learning. From email chains to the WWW (World Wide Web), from YouTube to Spotify, and from chat software to international video clips, learning that blends traditional teaching techniques with the range of e-media now available offers a range of new possibilities for the creation, evaluation, and transmission of knowledge.

We have also been chosen to receive computer tablets (Apple I-Pads) on loan from the College’s IT Service for each student during the entire semester. We use the tablets for access to open as well as library owned e-resources. Benefits of these resources will include cost savings for you, a rich array of open access and library sources, and the devices even encourage more use of traditional primary and secondary source materials. A liaison librarian–ours is Brenda Landis (landisb)–will assist us in identifying open access and library resources for our classes. Dickinson’s Library Database directory (including many full-text scholarly databases, streaming film collections, statistical sources, and digitized primary source collections) is available to you from the following link: http://www.dickinson.edu/homepage/584/ You should also see–and bookmark the direct link to the databases themselves: http://libguides.dickinson.edu/az.php.

NOTE: As a result of our grant-funded emphasis on blended learning and our loaned tablets, these learning resources will produce the need for students to be externally evaluated at various points during the semester. All students in English 212–Writing About Nature–will receive extra course-evaluation forms through their email. The Center for Opinion Research (COR) at F&M is developing pre- and post-course surveys for our class and other courses being offered at Dickinson this semester. The plan is to have all of this information delivered to you via your email; I ask that you please complete these surveys as soon as possible after you receive them. This results of your work in this program will make future classes at Dickinson better for you, for your classmates, and for many students who will come after you. Thanks in advance for your help with this project.

Electronic Tools for Writing About Nature

A streaming, edited blog of examples of the finest contemporary and current nature writing:

A site that describes the functioning of naturewriting.com (above):

http://naturewriting.com/about.php

A list of the best examples of nature writing:

https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/nature-writing

Paul Evans offers his analysis of effective nature writing:

http://www.discoverwildlife.com/competition-article/how-be-nature-writer

British author Richard Mabey defends nature writing against a recent attack:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/jul/18/richard-mabey-defence-nature-writing

A good overview of the genre:

http://grammar.about.com/od/mo/g/natwriterm.htm

A blog-site from the Henry David Thoreau birthplace historic site in Concord, Mass., near Walden Pond (your professor is a contributor):

http://thoreaufarm.org/theroost/

An interview with Bill McKibben via YouTube:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ofodxNPwOHM

A provocative article from Salon.com: the author argues that “nature writing is over”:

Essay Requirements:

–All essays must be typed: one-inch margins, double-spaced

–Assignments will specify a precise length for each essay

–Essays must be stapled or paper-clipped together

–Title page must include title, author’s name, and date

–Essays are due in class at 3:00 p.m. on the date indicated in the syllabus

–Final essays must be brought to class

–NO LATE PAPERS (or drafts) WILL BE ACCEPTED

See also Web Sites for Nature Writers: http://mosaics.dickinson.edu/naturalhistory2012/?s=212

Grading:

Essay 1 2 3 4 Rev #1 In-Class Journal Exam-Rev #2

10 10 10 10 20 10 10 20 = 100%

Students must complete all of these requirements to receive credit for the course.

_______________________________________________________________________

Class Meetings, Reading, & Essays Due: M Th 3:00 p.m., Kaufman 178 _________________________________________________________

January 19 M First class. 3:00 p.m.-4:15 p.m. Kaufman 178. Our syllabus as a text.

22 Th Blended Learning and IPads in and out of class (an introduction)

______________________

26 M Essay #1 due (a natural object: assignment sheet attached).

29 Th Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac. xiii-xix, pp. 3-137. Good nature writing?

______________________

February 2 M In-class exercise (sentences from student essays). Hacker, “Clarity,” pp. 1-19

5 Th Essay #1 revised (a natural object). Hand in for a final grade. Workshop.

_______________________

9 M Aldo Leopold, pp. 138 to end. Hacker, “Grammar,” pp. 20-56.

12 Th Annie Dillard pp. 1-148

_______________________

16 M Annie Dillard pp. 149-end

19 Th Vocabulary. Bring nature journal to class. Hacker, “Punctuation,” pp. 57-78

________________________

23 M Survey nature writing journals online.

26 Th Essay # 2 due (narration) Workshop. In-class: “To see the wind with a man his eyes.” Hacker, “Mechanics,” pp. 79-90

________________________

March 2 M Charles Fergus, Wildlife of Pennsylvania. Pick a single CAPITALIZED SECTION from this book [ex. COYOTE, ELK, PUDDLE DUCKS, WILD TURKEY, LAND SALAMANDERS, POND AND MARSH TURTLES, WATER SNAKE]). At the start of class, bring up a single-screen, double-spaced page about why your chosen entry in Fergus’s book is well-written, using examples of language as details; be prepared with notes on your IPad to tell the class why your entry is well-written.

5 Th Fergus, continue with examples in class. Submit Fergus paragraphs electronically.

__________________________

9 M SPRING BREAK

12 Th SPRING BREAK

__________________________

16 M Bring a well-written paragraph about nature from the web to class (on you IPad, linked to a page we can all access on our IPads, not a writer we are reading this term—submit your paragraph–electronically–at the end of class today).

19 Th Your field journal as a text. Bring you best paragraph so far, typed out on your IPad and sent via email to everyone in our class before class today.

__________________________

23 M More paragraphs from IPad journals.

26 Th Essay #3 due: analyze Leopold’s or Dillard’s style. Animal rights: class positions.

__________________________

30 M Ashton Nichols xiii-xxiii and 1-101

April 2 Th Ashton Nichols 103-end

__________________________________

6 M Fieldtrip to Farm – meet at Kaufman CSE lobby (next to Public Safety)

9 Th Field Trip to Reineman Sanctuary — meet at Kaufman CSE lobby

___________________________________

13 M Essay #4 (bring draft notes for Essay #4) Hacker, Glossaries, pp. 231-249

16 Th (No class: Research and Writing Day for Essay #4 and Revision of #2 or #3)

___________________________________

20 M Debate and discuss animal rights thesis statements: Animal rights online.

23 Th Blended Learning: A Conclusion

___________________________________

27 M 1st Revision Due in class at 3:00 P.M. (Essays 2-4)

30 Th Last Class, Essay #4 due (animal rights: interpretation)

———————————————————————————————————-

May 8 Friday FINAL EXAM (2nd Revision) due in Kaufman 192 by 5:00 p.m.

———————————————————————————————————-

Professor Ashton Nichols Kaufman 192 M TH 11:00 a.m.- 1:30 p.m. and by appt.

———————————————————————————————————-

ACCOMODATING STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES

Dickinson College makes reasonable academic accommodations for students with documented disabilities. Students requesting accommodations must make their request and provide appropriate documentation to Disability Services in Biddle House. Because classes change every semester, eligible students must obtain a new accommodation letter from Director Marni Jones every semester and review this letter with their professors so the accommodations can be implemented. The Director of Disability Services is available by appointment to answer questions and discuss any implementation issues you may have. Disability Services proctoring is managed by Susan Frommer at 717-254-8107 or proctoring@dickinson.edu. Address general inquiries to Stephanie Anderberg at 717-245-1734 or e-mail disabilityservices@dickinson.edu.

ACADEMIC HONESTY

The Dickinson plagiarism policy will be strictly enforced. This class adheres to the college’s Community Standards, which clearly state: “Students are expected to do their own work. Work submitted in fulfillment of academic assignments and provided on examinations is expected to be original by the student submitting it.” Please review the Community Standards document for more information. Please do not hesitate to ask me any questions you may have about citation, documentation, or academic honesty.

________________________________________________________________________

*****************************************************

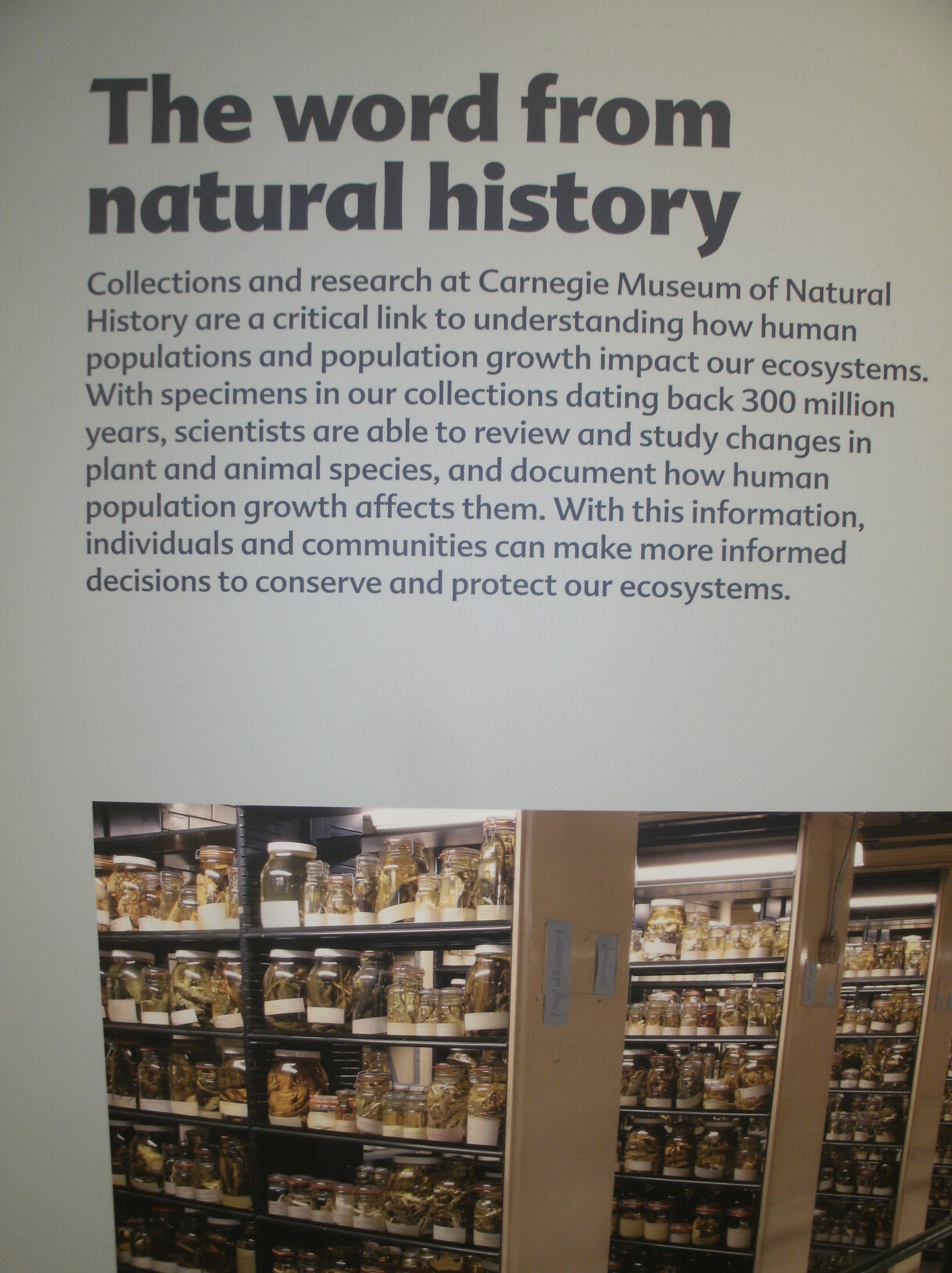

NATURAL HISTORY FIELD JOURNAL

For our “Writing About Natural History” class, you will keep your own natural history journal. It begins when you receive your “loaner” tablet IPad and ends on the final day of classes, when it will be handed in to me for the last time–electronically. This journal will describe, narrate, analyze, interpret and otherwise create an experiential and intellectual record of your experiences with the nonhuman world during our entire semester. This field journal will have no length requirement; it must, however, be complete. This journal can include days in Carlisle, days away from Carlisle, dreams you have had, solo experiences, group experiences, and conversations with your family and friends (Spring Break, week-ends, etc.)

You are encouraged to share your journal with your classmates, with other students, with professors, or with your family. You should feel free to ask me for advice or suggestions during the term, and you should feel free to copy “commonplace” selections into your own journal (that would mean quotes from Annie Dillard, Aldo Leopold, Charles Fergus, or your humble professor, as well as reading you are doing in any other class or simply on your own); just make sure that you always indicate when the words you write down in your journal are not your own. Consider all of our texts, classes, and discussions as source material for your own journal writing. Writing is a social and cultural practice. Your own writing always benefits when you see yourself as part of a reading and writing group of interested literate individuals.

I may collect these journals at any time during the semester. I may ask to see the journal—individually or collectively—on any day, maybe next Thursday! I may ask you to read aloud from your journal on any day our class meets. I may ask you to make use of your journal for additional formal or informal writing exercises. In short, this writing will be an ongoing component of your work for this class. In addition to your four formal (graded) essays and two formal revisions, this journal will form the basis for the bulk of your writing during the term. Let your journal be influenced by the other writing we do in and for class. Let your style be influenced by the readings we are doing and reading that you are doing for your other classes. Take advice from your classmates, or ignore it; take advice from me and your other professors–or ignore it!

Keep your journal in your IPad in a way that can be sent to classmates and to me in all or in part. We will share these journal electronically in class, and you will submit them to me that way. It must be written in your IPad tablet in journal format. Your journal should be work that you will want to read aloud–and will read aloud–to the class, or language that someone else could read aloud. I will collect these on Thursday May 30 for the last time and will hand them back to you after I have graded the Final Exam essays.

Let me know if you have questions.

********************************************

Essay #1

A Natural Object

Spend at least one uninterrupted hour observing a natural object. The object can be large (star, sun, cloud, mountain), small (grain of sand, flower, ant, leaf) or in between (stream, tree, turkey vulture, rock). Your object should be one that had not been shaped or visibly affected by humans. You should observe it as carefully as possible. Do not engage in any other activity during your observation. No Walkmans or electronic devices!

What did you learn as a result of this experience? Write a three to four typed pages essay that explains to the members of our class what you knew at the end of this hour that you did not know before your observation began. Write with care and attention to the precise details of your experience. Your essay should have a thesis (a central controlling idea) and a clear organizational principle (chronological, psychological association, logical progression). Avoid errors of grammar, syntax, and spelling. Proofread you work carefully.

This essay is due at the start of class on Monday, January 26 at 3:00 p.m. It should be typed, double-spaced, and should have a title page that includes a title that you have composed, your name, and the date. All essays in ENGL 212 will still be submitted in traditional paper format (typed, page numbers, stapled or clipped) for purposes of our regular workshop classes upon the submission of each essay.

This paper will be returned to you with my comments but no grade quickly; you will then revise and resubmit it for a final grade on

NO LATE PAPERS WILL BE ACCEPTED