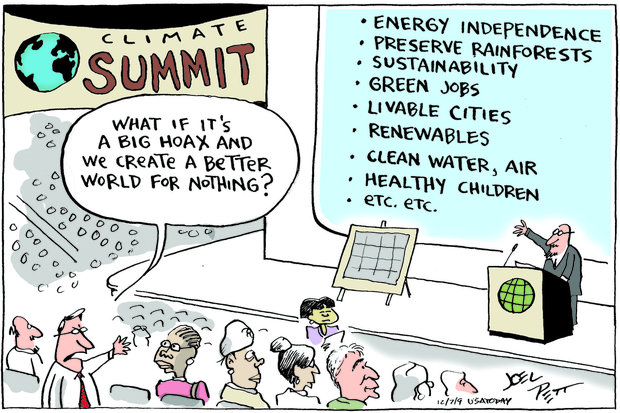

Definitions of risk are often framed around the possibility of harm. Decision-makers will never have 100% certainty, especially when it comes to climate variability. The UNFCCC does not allow incomplete data to limit global response. Instead, it follows a “precautionary principle” to adapt/mitigate climate change even when scientific certainty has not been reached. By their very nature, climate models simplify complex systems. Decision makers should respond to long term predicted changes in climate. Even if the models’ predictions do not come true, the actors have improved their resilience for future change.

From WikiCommons

Climate models in Nepal are imprecise about the magnitude of change but they are useful to understand variability. Uncertainty is even more of a reason to respond to climate change because many sectors – agriculture, trade, energy – rely on some level of predictability. If communities can anticipate variability, they may respond either reactively or resiliently. A reactive response plan would dynamically respond to any climate event depicted in the model. A resilient plan would build general structures to reduce the impact of any climate event – diversifying income sources, saving, or even moving. Without specific magnitudes, the stakeholders may not plan for specific events such as higher rainfall or a drought. A generalist approach to resilience based on uncertainty could be more useful to respond to more than just the coming crisis.

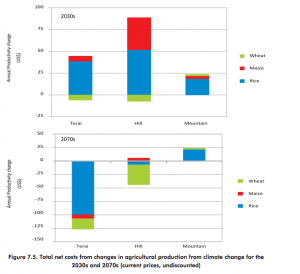

In the short term (2030), productivity and yields for some staple crops (maize, rice) may increase across Nepal. It is the responsibility of policy-makers to guide subsistence driven farmers and other actors toward the long term view – these crops will decline in productivity by 2070. These long-term decisions are difficult private actors that depend on individual harvests or bottom line profits. Policy-makers should institutionalize climate adaptation strategies even if climate models show uncertainty because uncertainty is still a threat to people (Zambrano-Barragán). Similarly, they should be able to critically analyze probability or hire personnel to do so.

From IDS Nepal

From IDS Nepal

Autonomous adaptation from people living and working in areas impacted by climate change should be facilitated by climate data. Policy makers can build institutional supports to encourage bottom-up adaptation with climate insurance systems, technical assistance, or infrastructure investment. These resilient systems are generalist in approach. They would mitigate the impact of any climate shock, regardless of certainty in the climate models.

Policy-makers and community actors should develop robust climate responses even if models are uncertain. If climate outcomes are less severe than predicted, the community will have bolstered its resilience for other, perhaps non-climate related shocks. If climate events are more extreme than anticipated, resilience systems will be better equipped. Climate responses are broadly sustainable. Conventional social support structures like insurance or infrastructure do not pretend to come from exact predictions of future outcomes. Neither should climate policy.

From Climate Action Reserve

Sources: